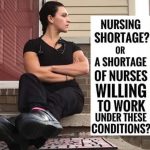

We came across a great metaphor about short staffing, finessed the wording, turned it into this image, and shared it on Facebook and Instagram. It was as if we’d opened the floodgates: your response was overwhelming. Almost a million people saw the post, and a torrent of heartbreaking stories and heartfelt frustration erupted into the comments.

“I wish I could clone myself to have some help,” wrote a nurse called Teresa (we won’t include the last names here of nurses who posted the most vulnerable comments): “It feels like we’re being set up to fail. We are stretched so thin as it is on top of being short staffed every shift. They can’t keep the new nurses they hire and the ones who have stuck it out are burning out. I can’t blame anyone that moves on for places with better staffing and pay. I just wish someone would hear us.”

“I feel so frustrated that I can’t just take care of my patients”

Too many comments — way too many comments — shared experiences that should alarm every American, let alone the policy makers who could do something about this. “They need to lower ratios for nursing homes too!”, warned Val:

“It’s 40:1 right now and there is no way that nurses can actually do their job correctly. It’s dangerous and charting is never accurate. There’s no time for anything except passing meds. You finish one med pass and it’s time for the second. If anything happens in between it puts everything behind. It’s dangerous for the patients and the nurse.”

“When I worked the nursing home it was 60:1,” another nurse chimed in, calling it insane: “I don’t know how i did it.. There was a few times I had 56 and I did nothing but pass pills for 8 hours. Nothing else.” True, another poster chimed in: “Once you get behind, there is no catching up … The fastest nurses were shoving the pills in crushed with applesauce and moving on. No water following them.”

It feels like we’re being set up to fail. They can’t keep the new nurses they hire and the ones who have stuck it out are burning out. I just wish someone would hear us.

Working conditions like these go beyond making nurses lose their joy in their profession, they endanger their very livelihood. “I used to LOVE being a nurse,” wrote Jill, “now [I’m] actually fearful for my license most of the time”. But of course such circumstances endanger the lives of patients even more, as research about nurse:patient ratios has stubbornly kept confirming. Just last month, a new study on nurse staffing in England “found that the hazard of death increased by 3% for every day” a patient experienced below-average nurse staffing levels.

“It was scary!”, wrote Sandra Hydrick about one nursing home she worked at:

“Too many patients on one nurse, they are all sick, on numerous meds, no way to do everything that needed doing. Couldn’t find needed equipment. It was awful. The patients need more care and attention than they are getting … I was running as hard as I could, not stopping for anything. I still felt I needed to do more.”

One of the most heartrending features of these stories is that nurses are some of the most motivated, selfless professionals you can find, and it pains them they cannot do their job adequately. “I love nursing,” wrote Joan Barrow George: “started as a nurse aide, LPN, AD then BSN now working on MSN”. But, she added, “I feel so frustrated that I can’t just take care of my patients”.

Short staffing, everyone agreed, puts both patients and nurses in danger. So why, then, did a campaign by Massachusetts nurses to enforce safer nurse-to-patient ratios fail so badly?

UMass Nurses #worcesterpride2018 #voteyeson1 #safepatientlimits #standbynursesnotadministrators pic.twitter.com/yIQX27bHfI

— Chercheur (@Chercheur63) September 8, 2018

The battle for better nurse:patient ratios

All the way back in 1999, California passed a law: hospitals were going to be forced to assign no more than a fixed number of patients per nurse. It took until 2004 before the details were hammered out and the legislation went into effect, but ever since the law has spelled out exactly how many nurses there would always have to be on hand.

The law takes into account the differences between specialties, and over time researchers have been able to measure its effects on nursing care. It has “resulted in roughly an additional half-hour” of nursing care per patient per day “beyond what would have been expected” otherwise, Matthew D. McHugh and colleagues found for Health Affairs. It did so without relying on nurses with lower qualifications, as critics had warned.

Ever since, nurse organizations like National Nurses United have fought to get other states to adopt similar laws. But all their efforts to persuade the politicians in state and federal legislatures ran aground in protracted procedures, as hospitals and other healthcare employers launched their rival lobbying drives. So the nurse union in Massachusetts, the MNA (Massachusetts Nurses Association), decided to take the question straight to voters. Ballot initiatives have seen voters pass minimum wage increases in states across the country even when politicians disagreed, so it seemed like a promising idea. Besides, ratios would not be entirely new to Massachusetts: the MNA and the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association already agreed in 2014 on mandated staffing ratios in ICUs.

The ballot question they presented would have set strict limits on how many patients any one nurse could be asked to cover. The limits would have varied depending on the hospital setting and how seriously ill the patients are: from one nurse per patient in intensive care to a maximum of four patients for medical and surgical nurses and no more than five patients at a time for psychiatric nurses. Hospitals could have been fined up to $25,000 per day for each violation.

Hues of red, white and blue

But straight from the start, not everyone agreed. The American Nurses Association, an influential professional organization with a less grassroots member base, joined employer organizations like the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association (MHA) and the Home Care Alliance of Massachusetts in opposition. So did the the Organization of Nurse Leaders, which represents nurse executives. Soon, confusion reigned supreme.

But straight from the start, not everyone agreed. The American Nurses Association, an influential professional organization with a less grassroots member base, joined employer organizations like the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association (MHA) and the Home Care Alliance of Massachusetts in opposition. So did the the Organization of Nurse Leaders, which represents nurse executives. Soon, confusion reigned supreme.

“The nurses union branded its ballot effort as the Committee to Ensure Safe Patient Care,” the Boston Globe reported. “Hospitals followed by calling their group the Coalition to Protect Patient Safety.” Both aired TV spots with nurses in scrubs to argue their case. “Both groups are promoting their messages via similar-looking websites, social media accounts, and lawn signs in hues of red, white, and blue.” The union had already created a Twitter account in 2013 called @PatientSafetyMA. When its opponents made one in 2017, they named it @MAPatientSafety.

Drowned out: funding counts

With the opposing messages and their sponsors muddled, the volume of advertising mattered. And opponents had access to a lot more funding. “What we know as political scientists is that it’s the groups that spend the most money that usually win,” Tufts University professor Jeff Berry told WBUR, and “in this case it [was] the hospital association of Massachusetts”.

The “Yes on 1” organizers spent $11.8 million. The “No on 1” campaign spent $26.4 million, and with nurses doing the talking in its commercials, the Boston Globe noted, “casual viewers might not realize that the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association is paying for the ads (unless they pause the video and scan the fine print)”. Advertising professor Tobe Berkovitz agreed that opponents made a savvy choice to use nurses as the face of their argument: “What the ‘No’ people have done is started framing the question as one where the nurses are the experts, and the nurses say no.”

It worked. An early Globe poll showed Yes leading by almost 20 points, and an initial MNA survey showed overwhelming support for patient limits among nurses. But public opinion shifted sharply during the campaign, and closer to election day a MassInc poll revealed that even nurses were evenly divided.

Acrimony among colleagues, fears of retaliation

The impact of the campaign was as invasive for nurses as it was confusing for others. Arguments among colleagues became increasingly bitter. The MassInc poll showed how they broke apart depending on their own working conditions: “Nurses who say they’re going to vote no are more likely to be very satisfied with their job [and] they’re less likely to say they feel overloaded or have too many patients”. Half the polled nurses agreed that mandatory ratios would improve patient safety, but almost one-in-three believed it would change little or create mixed results, and most of those turned against the proposal.

Supporters of the ballot initiative grew increasingly fearful of retribution from their employers and insisted on being quoted anonymously in news reports. “Nurses for and against the ballot question called WBUR to report feeling bullied by the opposition,” the radio station reported, “although we received more complaints about hospital managers harassing nurses”. Angry Yes activists tweeted photos of hospitals scaring patients with No posters. A hospital which sent out election mailers to patients in envelopes marked “TIME SENSITIVE” raised questions whether it used confidential medical records for political reasons, unduly scaring people who thought they were getting bills or medical information.

The No campaign accused Yes ads of peddling misinformation about survey data and research findings. But nursing professor Judith Shindul-Rothschild told The Nation it was the hospitals which had spread “misinformation and fearmongering”. Even backers of the campaign ended up feeling a ballot initiative might have been the wrong tool. “I’m really upset about it, I’m ready to cry,” a nurse who voted Yes told WBUR. “I just feel like we’re at a loss and we’re kind of defeated.”

Learning lessons from Question 1

In the end, it wasn’t even close. The ballot initiative was defeated by a 70% to 30% margin. Northampton was the only county of significant size where a (bare) majority of voters said Yes.

Supporters will be regrouping in early January to discuss what to do next. Elsewhere, for example in New York and New Jersey, nurse activists remain determined. But if they failed in Massachusetts, what chances do they stand elsewhere? Are there any lessons we can learn? How did they lose the argument? Opponents presented three arguments that persuaded many voters, including nurses: total cost, negative consequences for smaller facilities with fewer resources, and unrealistic planning.

Cost

The Massachusetts proposal set higher standards than the California law. Union officials argued that implementation would only cost $47 million, but a report by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission (HPC), an independent state agency which monitors health care spending, suggested an intimidating total annual cost of $676 million to $949 million, estimating that Massachusetts might need more than 3,000 additional nurses. An MHA-commissioned study even put the number at 5,911 additional RNs. The Yes campaigners decried the HPC study’s methodology, but it seems to have played a key role in making even many nurses skeptical of the whole venture.

Supporters of the ballot initiative argued that the new measures would partly pay for themselves. Not just because hospitals would pay less overtime, but because they would avoid the significant costs they now face having to recruit and train ever new nurses, because so many professionals leave bedside nursing or burn out because of staffing conditions. Improved staffing, nursing professor Linda Aiken explained to The Nation, also result in reduced overall healthcare costs because fewer patients end up in intensive care, or suffering serious issues after discharge. Having researched the effects of California’s legislation, she concluded that “better-staffed hospitals with good work environments actually returned lower mortality for the same or lower cost”.

To the extent significant investments would still need to be made, “Yes” backers also pointed at industry profits of $7.5 billion statewide over the past five years, and funding that’s now going to capital investments and other overhead costs that could be used to hire more nurses. MNA’s message about the half dozen chief executives of Massachusetts hospitals and health systems who receive financial compensations that add up to $2-5 million annually was echoed by some bedside nurses. “At my hospital, our CEO makes a multimillion dollar salary, where nurses at night can be forced to care for 7-8 patients,” one RN remarked bitterly.

But those arguments were either less persuasive or drowned out, and the costs argument loomed large. Even a majority of the nurses who said they’d vote Yes agreed that it was at least somewhat likely that hospitals would pass the expense on to insurers, meaning that premiums would rise.

Vulnerable facilities

Opponents warned that health care facilities would have to shutter services and institutions, for example in psychiatric care, because they would be overwhelmed by the costs of hiring and training enough nurses to meet the new regulations. The No campaign threatened that “this costly unfunded proposal” would force hospitals “to make deep cuts” to opioid treatment services and force “many community hospitals … to close”. Healthcare facilities told nursing schools that student clinical placements could not be ensured if the initiative passed.

The Yes camp accused them of scare tactics, but the message resonated. The MNA argued in vain that the law obliged hospitals to meet the ratios without reducing their “level of nursing, service, maintenance, clerical, professional, and other staff.” Half the nurses surveyed by MassInc believed that the ratios would end up with hospitals closing units or closing altogether. The argument that hospitals, looking to meet their ratios, would end up hiring nurses away from their current jobs at institutions which would then be left in trouble resonated as well.

“They’re going to have to pull nurses away from mental health beds, and the state is short on mental health beds already,” ICU nurse Caitlin Hamel told WBUR. Even as some of the largest hospitals were spearheading the No campaign, nursing workforce researcher Karen Donelan actually argued that “the big hospitals will win … if Question 1 passes”.

Massachusetts Voters: Please vote No on Question 1, re: mandating nursing ratios. It’s a well intended bill with so many faults and unintended negative consequences for patient care. .@MassGeneralNews nurses shout from the rooftops pic.twitter.com/UyyLoL0FK4

— Rebecca Inzana (@RebeccaInzana) October 27, 2018

When it comes to a subject that sounds as technical as nurse-to-patient ratios, even if it will affect every one of us at some point in our lives, voters will listen to nurses – it’s the most trusted profession of America, after all. But what when nurses themselves sound divided? Alanne Duger, a retired teacher who spoke to WBUR afterwards, said “friends who are union nurses at some of Boston’s larger hospitals urged her to vote for the staffing ratios, but other friends who work in smaller community hospitals or on psychiatry wards lobbied for a “no” vote”. She added, wistfully, “when you have so many nurses who aren’t clear about the stance it makes those of us who aren’t nurses question it as well”.

How much, how fast?

Many nurses also didn’t seem to recognize themselves in the specific ratios that were being proposed, or at least that’s what the MassInc poll suggested. By definition, it’s easier to agree with the need for patient limits in general than to approve of every count in an elaborate roster of specified ratios. “There’s no consensus among nurses … about how many is enough,” WBUR reported. “38 percent of nurses don’t agree with many or any of the proposed ratios.”

Nurses like Caitlin Hamel were also persuaded by the argument that “the ballot measure is not realistic because the ratios would take effect on Jan. 1, giving hospitals less than two months to staff up”. California’s law allowed more “time — five years! — for implementation,” Donelan pointed out. Where would so many new nurses come from, so quickly? “The immediate need for additional nurses would not have been matched by an expansion of nursing’s educational pipeline, which is already struggling with a faculty shortage,” nursing professor Judith A. Vessey argued in a postmortem.

“The status quo is not a solution”

Many of the businesses and institutions that opposed these nurse:patient ratios would have done so anyway. But could more people who were now on the fence be persuaded to support mandated ratios with improved proposals and messages? If the organizers have the more authoritative assessments on covering the costs on their side? Or the proposal covers enough of the healthcare sector to avoid pitting hospital nurses against nurses who work elsewhere? If not, what’s the alternative?

Some of the “less complicated” solutions Vessey suggested, which focus on things like increasing nurse representation on company boards and hospital transparency about their nurse staffing and turnover, seem vague or offer little that hasn’t already been tried. As alternative to legal obligations, a focus on transparency risks placing even more of the burden for ensuring adequate care, and finding and sorting through complex information to do so, on the patient. A focus on company boards might underestimate the risk of token nurse leaders being co-opted. But whether laws about ratios are the solution or other measures can be enough; whether they are fought at the ballot box, in political lobbies, or in negotiations between employers and nurses; something will have to give. “The status quo is not a solution,” MNA president Donna Kelly-Williams said after the initiative lost.

Standing in solidarity with @PatientSafetyMA for the #YESon1 campaign for #SafePatientLimits this afternoon! #mapoli pic.twitter.com/ykziCLJGax

— Mike Connolly (@MikeConnollyMA) November 1, 2018

Blogger EDNurseasauras will agree. An ER nurse with 40 years experience, she walked her readers through a recent shift. Patient by patient, step by step, she described how she rushed through the bare minimums of what is needed, as efficiently as possible, businesslike by necessity, and still fell behind further and further. She describes being left with a feeling of failure:

“I am back at my desk now about 57 minutes in and I haven’t even laid eyes on the 4th patient. I have done nothing but toilet a patient who isn’t mine, clean up shit, give meds and fluids. I have done nothing, really, to educate my patients or make them more comfortable, or even make them feel like I care about their problems.”

Her conclusion:

“At this point I completely understood why Massachusetts nurses put this on the ballot, born of utter frustration. More nurses, better care … If I lived in Massachusetts I would vote yes.”