That sinking feeling. “Not again.”

Parents know it all too well, nowadays, when yet another school shooting hits the news. But now nurses increasingly do as well.

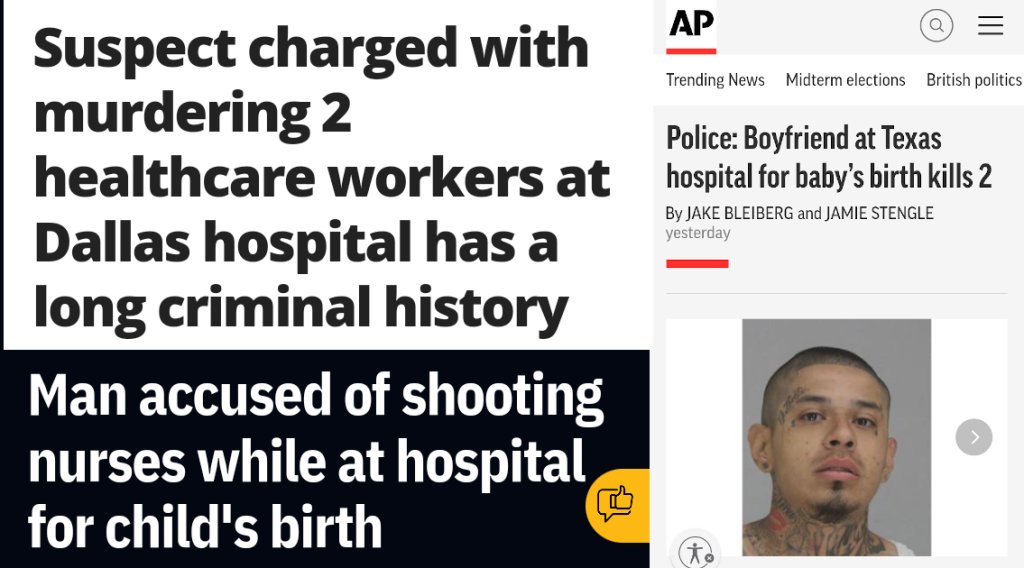

Last week, 30-year-old Nestor Hernandez, who was already on parole for an eight-year aggravated robbery sentence, opened fire in the maternity ward of Methodist Dallas Medical Center in Dallas. He killed 63-year-old nurse Annette Flowers and 45-year-old social worker Jacqueline Pokuaa.

Despite spending 100 days behind bars this year for parole violations, Hernandez had been allowed to visit his girlfriend for the delivery of their baby. After a paranoid argument, he “pulled out a handgun and hit his girlfriend multiple times in the head with it,” and told her that “whoever comes in this room is going to die with us.”

Pokuaa and Flowers died for no other reason than that they were the first to enter the room, looking to help.

The incredible and infuriating thing is that they were not even the only healthcare workers to die a senseless death at work that week. Literally days earlier, psychiatric nurse practitioner June Onkundi was stabbed to death by one of her patients in Durham, North Carolina.

She was about to start a doctorate program in January — a promising career cut short, a family left bereaved. “She made a difference for every person and every heart that she touched,” her grieving brother-in-law said.

We cannot go on like this. Nurses who already face grueling working conditions cannot go on like this.

Have you or your colleagues suffered violence from patients or families? Do you feel like your supervisors and managers responded adequately? What more do you think could be done? Share your story in the comments below! (Or share our Facebook / Instagram / LI / Twitter posts and add your suggestions.)

For years, nurses warned about a surge of abuse and violence. Then the pandemic hit.

There are almost as many violent injuries in the health-care industry “as there are in all other industries combined,” we wrote after a horrifying shooting spree at Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center in New York City in 2017. Violence against nurses and other health care workers has been rising by frightening degrees for years. And nursing organizations have been warning for just as many years that the threat is getting out of hand.

As the Texas Tribune warned last year, “health care workers have faced rampant violence in the workplace” for decades… but the rate of violence further increased by more than 60% between 2011 and 2018. Health care workplace violence is “underreported, ubiquitous, and persistent,” yet also “tolerated and largely ignored,” the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) sternly pointed out all the way back in 2016.

Stunningly, there were over 150 shootings inside or on the grounds of American hospitals between 2000 and 2011 — and that’s not counting the ones that caused no injuries!

Yet little to nothing was done to make nurses safer.

And then, piling on the pressure, the pandemic erupted, supercharging risks for nurses as its strains and anxieties flooded into hospitals and clinics. Even as they were celebrated as healthcare heroes, front-line medical workers were “routinely scratched, bitten or verbally abused by patients”.

Terrifying stories that didn’t make the national news showed up over and again in local media. “He attacked me – he leaped from the chair. He tried to gouge my eye out with his key. It’s horrible! You’re trying to help somebody and they try to kill you. Because there’s no doubt in my mind that if I didn’t get rescued he would have killed me,” a Massachusetts RN told 7 News Boston.

“I have been followed and chased. I have been threatened with battery. I have been threatened with rape. I have been hit in the face. I have been spat on and I have been spat at. All of these things have left me emotionally and physically scarred,” nurse DeBreisha Flowers-Anderson told WTTW in Chicago.

In Hawaii, the nurses union HNA reported that nurses had been “punched in the face and given black eyes or split lips”; one pregnant nurse was “knocked-out cold from a punch.”

Though it played no role in last week’s attack, fear and anger about Covid-19 has played a major role in the further escalation of violence. Nurses who work with COVID-19 patients are “more than twice as likely to be physically attacked or verbally abused at work than those who care for other patients,” workplace violence researcher Jane Lipscomb found. Controversies over masks and vaccines fueled a new surge of abuse, accelerating “the problem of violence towards healthcare workers.. at an alarming rate”.

Soon, nurses and doctors were blamed for the very pandemic itself. Vaccination teams were harassed and events shut down or canceled “due to threats against the safety of the staff”. People showed up at hospitals to scream at healthcare workers. Doctors and nurses were accused of secretly killing patients for government payouts. Georgia’s top health chief Dr. Kathleen Toomey “burst into tears over the harassment and vitriol spewed at health care workers”.

In the crosshairs: healthcare workers face unique risks

No wonder that almost half the hospital nurses the NNU surveyed this year said workplace violence had increased — a number that itself has been increasing across several recent NNU surveys.

Visitors and patients assaulting hospital staff “was an epidemic before the pandemic — it was just silent to the public,” said Karen Garvey of Parkland Health & Hospital System in Dallas. Now, shootings like last week’s are revealing to the public how bad it is.

The official statistics are staggering:

- “Health care workers are four times more likely to be verbally or physically abused than workers in private industry”.

- They are five times “more likely to suffer a workplace violence injury than workers overall”.

- And the rate of serious violent incidents they face “is more than four times greater than for those in other industries”.

- All the way back in 2006, the health care sector already represented almost half “of all nonfatal assaults against workers resulting in lost work days in the US”.

Nurses themselves have been through this so long, they have rung the alarm over and over again:

- A massive 82% of Texas nurses surveyed by state health officials in 2016 reported being verbally abused and “nearly half also reported physical violence like being hit, slapped or choked”.

- 54% of ED nurses told an Emergency Nurses Association survey in 2011 that they had been the victim of violence on the job within the past seven days.

- A full 80% of all hospital staff say they have been assaulted at least once in their career, according to a Georgia state Senate resolution last year.

The sad paradox is that what makes our job so dangerous are the very patients we’re here to help.

Steve Edwards, the President of Missouri health system CoxHealth, estimated that 80% of the assaults are coming from patients. It’s a tough environment. We “have to give bad news to patients or family already in extreme pain or emotional distress”. We work with people who suffer from addictions or mental health issues.

The most common characteristic among perpetrators, the NEJM study found, is “altered mental status associated with dementia, delirium, substance intoxication, or decompensated mental illness”. So it’s unsurprising that the ER and psychiatric wards are the most violent.

But violence in other departments may be underreported because there just isn’t as much research about it. Nursing aides and home care workers are at serious risk too. Half the nursing home aides have been physically injured by a patient, the NEJM added; more than one in six had required medical attention.

And to some extent, that all makes sense — a tragic, inexcusable amount of sense. But why has the violence kept getting more frequent, and more serious, even before the pandemic?

Understaffed, a system straining at the seams is worsening the violence

The man who shot Annette Flowers and Jacqueline Pokuaa was incredibly disturbed and violent, a man who should have been behind bars. He did not kill because of anything that was happening in the hospital.

But the general trend of increasing verbal and physical violence against healthcare workers is very much related to the stress the system is under. The NEJM article already identified things like long wait times and crowding as risk factors which add to simmering tensions that can boil over any time.

The longer the wait for care, the more restless people become, the chief of emergency medicine at Northeast Georgia Health System told Georgia Public Broadcasting. “I think one of the big causes of this is that our resources are taxed in a way that they’ve never been taxed before”.

When Gene Morreale, the CEO of Oneida Health in upstate New York saw that his modest 101-bed hospital had recorded more than 40 cases of physical and verbal abuse against staff in one year, he decided to write a letter directly addressing patients and visitors, telling them:

“There are times when you as a patient are struggling and perhaps feel that the healthcare system is not doing enough for you or your loved one. I understand that happens, but it does not get fixed by being physically or verbally abusive.”

But heartfelt pleas to frustrated patients will not solve this crisis. For that, we need action.

There is no lack of ideas. Hospitals have come up with makeshift measures. Legislation has been proposed. Experts have pointed out the changes that are necessary at the management level. But what is missing is urgency.

Which is incredibly weird, especially after this pandemic. What could be more urgent than the physical well-being of the people who take care of us all?

What hospitals have tried doing — and why results have been mixed

Some health systems, to their credit, have experimented with different responses. Cox Medical Center Branson gave hundreds of staff a panic button on their badge after reports of staff assaults had tripled. They weren’t alone: hospitals across the nation have started giving nurses panic buttons.

Parkland Health & Hospital System in Dallas appointed six mental health peace officers trained in responding to high-risk incidents. They also developed a system to flag patient records when patients are known risks to staff and purchased “wearable alarm systems for employees that can emit a piercing noise if they need help and are not near a panic button”.

But they are flailing, and some of the solutions just underscore how grotesque the threat has become. Lipscomb suggested choosing “waiting room furniture that can’t easily be used as a weapon.” And Cox Health brought in trained German Shepherds. “If need to they can attack,” Edwards explained, but “we haven’t had to do that because I think most people understand the threat of a dog”.

It’s also uncertain if arming security guards better would help. A critical care nurse on Reddit argued that, for mass shooting events, “the best defense is another gun… the attacker does not stop unless shot by police or an armed citizen”. But there is evidence “that in 10% to 20% of gun-related incidents in hospitals, the perpetrator took the gun from a security guard”.

Hospitals have preferred focusing on enrolling nurses in de-escalation, self-defense and safety trainings. The federal government got in on this as well, with the CDC offering a Workplace Violence Prevention course for nurses (which at least earns you continuing education units!). But it isn’t clear whether this approach actually helps either.

Morreale admitted that, in his hospital, they posted signs and gave staff de-escalation trainings “yet the aggressive, inappropriate behavior continues”. The NEJM study found that nurses who received training “had increased confidence and knowledge about risk factors,” but no actual change “was seen in the incidence of violence”.

A lot of nurses also understandably scoff at these trainings because it seems like a transparent example of employers offloading the responsibility for preventing workplace violence squarely on the shoulders of the overworked nurses, rather than focusing on what they can do to protect them.

Has your hospital taken any specific measures to prevent or combat violence? Do you feel they have worked? Let us know in the comments!

If you don’t listen to nurses, they stop telling you how bad it is

It’s maybe no coincidence that hospitals have generally shied away from the beefier recommendations in the NEJM study. Because those are about pervasive understaffing — and showing nurses that management is reliably on their side.

“Perhaps most important,” it concluded — and we’ll put part of this in bold — “are recommendations that health care organizations revise their policies in order to improve staffing levels,” provide adequate security and mental health personnel on site, and intervene with supervisor support as soon as threats appear.

Our reality is a far cry from all that. All too often, hospital management “simply throw their hands at us”. A quarter of nurses say their employer is “not at all or only “slightly effective” at managing workplace violence”. When violent incidents happen in the ER, Chris Kang of the American College of Emergency Physicians explained, “some hospitals simply don’t want to proceed with charges; other times, law enforcement does not follow up”.

In one Hawaii hospital where nurses were alarmed by “ridiculous nurse and patient ratios” and an “absolute lack of security,” they demanded a zero-tolerance policy instead of the gaslighting they received:

A Hale Pulama Mau nurse who wants to remain anonymous says she is physically or verbally abused every day, including incidents where she’s been punched in the ribs and eye. “This patient, in particular, likes to scratch, likes to dig the nails. You’re told ‘Oh, just put socks on. Put socks on your patient’s hands.’”

“Almost every one of the nurses that I’ve spoken to who’ve been victims of abuse, either sexual or physical,” Hawaii Nurses Association President Daniel Ross explained, told him that management had questioned them: “Oh, what could you have done better in that situation? What could you have done that wouldn’t lead to that moment?”. It’s ”basically blaming the victim,” he said.

One consequence of this kind of attitude is that we don’t even really know anymore how big the problem actually is, because nurses don’t bother reporting it — or don’t feel safe to do so. “The actual number of violent incidents involving health care workers is likely much higher” than the statistics suggest, the Joint Commission concluded. Official data are likely “grossly inaccurate”.

Even hospital systems which actively tried to get their staff to report all incidents of violence have struggled because people “basically felt that that’s just part of the job”. Some nurses struggle with sympathy for the offending patients, reluctant “to blame or shame violent patients who are ill or affected by medication”. But most of all they think, “Nothing ever happens when I report so why should I bother?,” as Professor Judy Arnetz told the Texas Tribune.

No more improvisation and gaslighting. We need real solutions!

All institutions, not just in health care, love to focus on processes and paperwork. But replacing voluntary procedures with mandatory reporting seems like putting the cart before the horse. Nurses need to feel like reporting serves a purpose — otherwise it’s just another pointless hoop to jump through. Above all, they need to feel that it’s safe to report assaults without worrying about retaliation. Because yes, that happens!

The NEJM called it already six years ago: what is at stake is accountability:

Nurses have cited fear of retribution from supervisors, the complexity of the legal system, and disapproval of administrators as barriers to the reporting of workplace violence.

Specifically, they cite a lack of management accountability toward such reporting and contend that the current intense focus on customer service in health care serves as a deterrent to reporting workplace violence, since … “the customer is always right.”

Until these impediments are removed by health care institutions, by legislation, or by public demand after another highly publicized attack, we should not expect a major change.”

The government implicitly told employers the same thing, when the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) outlined risk factors in their Road Map for Healthcare Facilities. There’s nothing much anyone can do about working in vulnerable communities or with troubled patients, but these risk factors stand out:

• Working when understaffed in general—and especially during mealtimes, visiting hours, and night shifts.

• High worker turnover.

• Inadequate security and mental health personnel on site.

• Long waits for patients or clients and overcrowded, uncomfortable waiting rooms.

• Perception that violence is tolerated and victims will not be able to report the incident to police and/or press charges.

Employers shouldn’t just take this advice to heart out of a sense of duty or ethics. This problem will seriously affect their bottom line too. Victims of workplace violence are left with “injuries, psychological trauma or decreased morale,” may “trust their employers or coworkers less … or even leave the profession,” and suffer increased rates of missed workdays, burnout and decreased productivity.

As William Buchta of the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine said at a conference this year: “Do we really need another reason for healthcare workers to leave the field?”

Taking our fate in our own hands? When nurses stand up to violence

Some healthcare workers have had enough and actually took to the streets. Nurses at the University of Illinois Hospital protested outside the hospital last year, launching a picketing campaign supported by their union, the Illinois Nurses Association.

They said “violent incidents at the emergency department, exacerbated by staff shortages, are creating unsafe conditions” — and that 18 nurses had left just that past year because of how unsustainable and dangerous the situation was.

Others have stressed advocacy — and having each other’s back. “We must become our own advocates,” hospitalist Giancarlo Toledanes wrote. “We should alert local, state, and health system leadership to the violence against healthcare workers. We should demand increased protection for our most vulnerable colleagues.” But in the meantime, “we must be mindful of compassion fatigue” and burnout, and “lift each other up … when our colleagues need help.”

Trevor Wolfe of the Missouri Nurses Association, who was punched in the face multiple times in one year yet still thinks “nursing is an amazing profession,” said: “I’m definitely not gonna tell anybody to run away. But I will tell you to stand up, and do not accept workplace violence”.

But how can individual nurses be expected to take that on by themselves? Like, what — lobby the state or federal government after your 12-hour shift? That’s where nurse unions and associations have tried stepping in, though they need your support to do so.

After the death of one of their members, National Nurses United (NNU) successfully lobbied for new Workplace Violence Prevention laws in California and Minnesota, and then focused on petitioning the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Its news and resources page on workplace violence prevention includes a call to “send a message” to Congress.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) launched an #EndNurseAbuse campaign to call for “enforceable “zero tolerance” policies”. They’ve collected 32 thousand signatures and are still asking you to share the End Nurse Abuse pledge. They published some resources too, including a whole book about How to Take a Stand Against Violence in the Work Setting if you feel like digging in, though it’s not free.

Likewise, the Emergency Nurses Association worked with the American College of Emergency Physicians for an awareness-raising campaign called “No Silence on ED Violence,” with social media pages and hashtags, educational and training resources, and a call to join them.

Rules and regulations: the long fight to legislate nurse safety

But does any of this awareness-raising actually help stop the violence? How much can a hashtag do?

You can’t help but wonder. That’s why a lot of the focus of all this advocacy has been on lobbying policy-makers for new legislation. After all, in the end, if hospitals are to be forced to take the kind of measures that many have rebuffed, there is little alternative.

But we have to be honest here: it’s been a slog.

First of all, it’s outrageous that there is still no federal legislation that specifically addresses the violence we are facing. But to be fair, it’s not for lack of trying! After years of lobbying and advocacy, the US House last year passed the “Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act,” which would require healthcare employers to implement a comprehensive workplace violence prevention plan.

It wasn’t just the NNU and the ANA which had been pushing for it, smaller groups like the American Psychiatric Nurses Association were on board too. But similar to bills about nurse-patient ratios, the American Hospital Association (AHA) lobbied to block it, saying it would be too expensive. And although all the House Democrats and several dozen Republicans voted for it, the bill has been stuck in the US Senate ever since. The NNU hasn’t given up, and is asking you to sign their message to Congress.

Parallel to this, the Safety from Violence for Healthcare Employees (SAVE) Act was introduced in the US House this summer and has 48 co-sponsors from both parties, and the AHA does support this one. If passed, it would criminalize assault and intimidation of healthcare workers.

Finally, there is another federal route that could get us those requirements for healthcare employers, and they’d have to involve employees. After years of work and setbacks the OSHA might finally issue a draft standard early next year that would make it a lot easier to enforce anti-violence measures. That might have more effect than the new workplace violence prevention standards which the Joint Commission established this year.

In the meantime, nurse organizations have been looking at the states instead for legislation to require employers to run workplace violence prevention programs. Not entirely without success: according to the ANA, eight states now have them, including Illinois, Oregon and Washington. Or take Louisiana, for example. They have a new law on the books named after Lynne Truxillo, a nurse who died after being attacked by a patient. It increases penalties for perpetrators and imposes a series of obligations on health care facilities, diligently summarized by New Orleans City Business. One of them specifically prohibits “retaliation against employees who report acts of violence”.

The ANA also mentions that almost 40 states have passed or amended laws about assaulting first responders to make sure they specifically include nurses or health care providers and/or increase the penalties. But in some states this only applies to ED staff. In Texas, for example, state politicians passed a law back in 2013 that made it a felony to assault an emergency room nurse, but “legislation that would have expanded that to include nurses in other areas of a hospital died in the Texas Senate”.

There have been some glimmers of hope elsewhere, like a new law in Missouri which “allows nurses who press charges to remain anonymous,” KY3 reported. They quoted an ER nurse, Becky Fleming: “You don’t feel like someone is going to be hunting you down to find out where you live”.

But a lot of draft legislation, from Massachusetts to Georgia, seems to get stuck somewhere along the way, winding through committees. And it can be hard for nurses to grasp if it’s just that the process is slow, or the bill has hit a roadblock and has been quietly parked it away indefinitely. Hell, it’s hard for us too, and if you have updates or corrections please let us know!

What do you think matters most right now?

NurseRecruiter.com is just a specialized nurse job board. We help you find the job opportunities you are looking for — we don’t have a special ‘in’ when it comes to the halls of Congress either. But the size of the problem is spreading and growing far too fast for any of this to be enough! Not the meandering processes in Washington, DC. Not the halting experiments by managers and CEOs.

Whichever nurse association or union you prefer, the NNU or the ANA or your state nurse organization — let’s join their efforts to push and pressure the politicians and the companies to do more. Sign those petitions, share those info sheets and resources, even use the hashtags just in case that might help with anything. Share this blog post on your social media accounts. And donate to the Gofundme pages for the bereaved families of Annette Flowers and June Onkundi.

Finally, tell us here or on our Facebook, Insta, Twitter or LinkedIn posts what you think matters most right now! Should there be gun bans in hospitals, or would that actually make things worse? Should there be dedicated security for individual units? More emergency drills for active shooter situations? Bottom line — what is the single most important thing, according to you: Understaffing? Security staff and panic buttons? More trainings? A zero-tolerance policy which lets you know that management has your back?

If you reach out to your supervisor and say that you are worried about a situation like in Dallas happening to your colleagues, what response would you get? Karen Garvey called assaults of hospital staff a silent epidemic. Silent things get ignored. So we need to keep breaking that silence, and insist on being heard!

Grace Ndungwa

The abuser is verbally abusive for many hours before attacking and the management does nothing,they just pamper them and call them honey,one even washed a verbally abusive ones hair to calm him instead of telling him not to abuse nurses he called us whores and throwed punches for 3 weeks he had insight

Rahul Iyer

Help nurses

Denise Hedgecock

This has been going on since I started in nursing in 1972. ADM doesn’t do anything. From administrators to Unit managers. Security is a joke. They don’t respond. Family /patients aren’t charged with threatening or physical violence. I’ve been threatened, propositioned, kicked, had objects thrown at me and falsely accused. And exactly… “what did you do to cause this reaction”?