Coronavirus is not over. The crisis response jobs are still there, and they pay well! We can help you find those nursing jobs. But we have to be honest about the costs too.

We need urgent action to protect nurses better. Not just because many nurses are, incredibly, even now, still not getting the PPE they need. But because we are seeing the sheer scale of the mental health problems Coronavirus care is inflicting on them.

We will start with the news about the jobs, and where they are likely to show up next. But then we want to talk about the trauma experts who are ringing the alarm bells. Healthcare workers, Prof. Neil Greenberg warned, are “at risk of high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder if they don’t get the right support”.

Nurses are hurting. And if they are not better protected now, it will bite employers in the back too. Because they will still very much need nurses who are ready to step into the breach.

“Everybody is competing for travel nurses right now”

“If you are a nurse currently working in a non-hospital environment, a retired nurse or another retired healthcare worker … help us care for our community during these historic times,” Matthew Upton pleaded just two weeks ago.

He is the CMO of Thomas Health in Charleston, West-Virginia, and his message is blunt: “Our hospitals need additional nurses, not additional beds”.

Even this late in the Coronavirus crisis, you will hear those words over and again. Earlier this month, it was the President of the Alabama Hospital Association, Dr. Don Williamson, who said almost the same thing. “The issue for us is staffing. It’s not beds or ventilators.”

Alabama hospitals “continue to care for hundreds of COVID patients” even as the summer’s surge faded, “and many employees are exhausted,” WBHM reported in early September. Will Ferniany, the CEO of Alabama’s largest hospital, said it was down several hundred nurses.

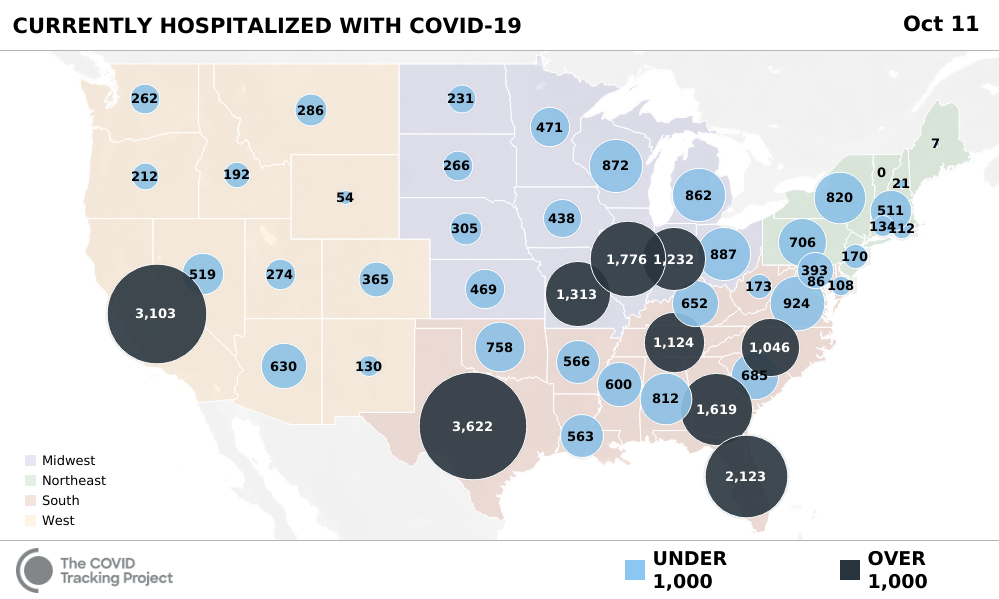

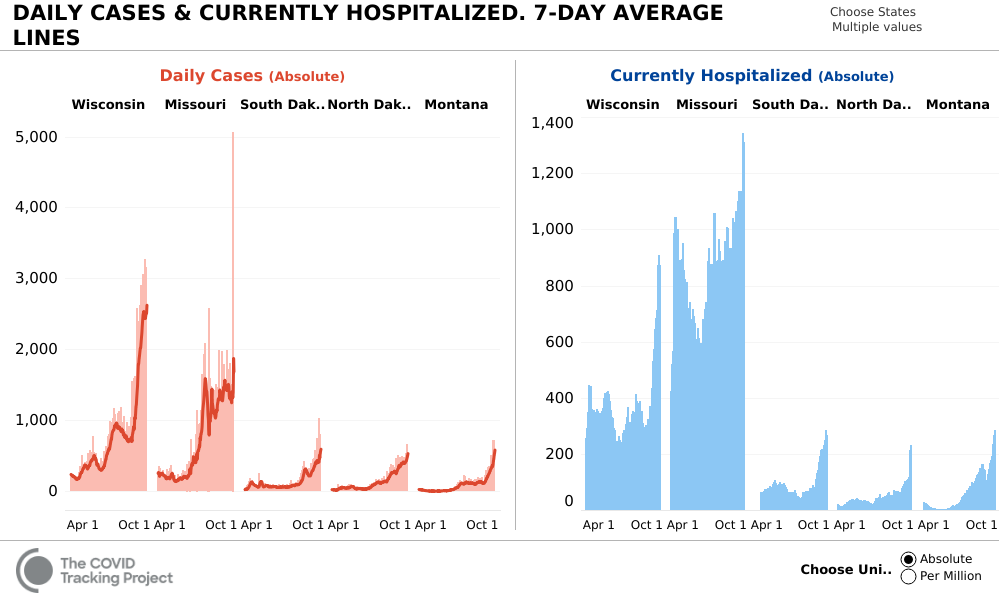

Right now, the number of new cases in the US “has risen for three weeks in a row,” the Covid Tracking Project blog warned. After two months of gradual declines, “the number of people hospitalized with COVID-19 also ticked up this week for the first time since mid-July”.

Wisconsin is being hit particularly hard, and “hospitals have been especially overwhelmed in Green Bay, Wausau and the Fox Valley,” the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel reported. Health officials said this week that “Wisconsin is closer than ever to opening a state-run field hospital due to the surge in cases”.

Among states with smaller populations, the Dakotas and Montana have seen sharp increases in hospitalizations as well as cases too. They’re rising sharply again in Indiana and reached a new high in Missouri.

As COVID-19 numbers wane in some states, they surge in others — that’s a pattern which is likely to continue for a considerable time. And so, ever new states are suddenly grasping for ways to recruit new healthcare staff.

For that, hospitals are looking at travel nurses. Critical care nurses are in particular demand. Ironically, the demand for travel nurses is so high that some nurses have left their regular jobs to take up better-paid travel nursing, WBHM observed, increasing the nursing shortage at their hospitals.

As COVID-19 numbers wane in some states, they surge in others — that’s a pattern which is likely to continue for a considerable time. And so, ever new states are suddenly grasping for ways to recruit new healthcare staff.

In late August, it was Hawaii’s turn to be slammed by a Coronavirus surge, leaving health care providers and state authorities scrambling to find more nurses. It was the same familiar refrain, the Honolulu Star Advertiser reported: there were enough beds — more than 3,000 — but hospitals only had the staff to cover 2,000 of them.

“What we don’t have is staff,” said Hilton Raethel, CEO of Hawaii’s Healthcare Association.

“Everybody is competing for travel nurses right now,” sighed Mimi Harris, chief nursing officer at The Queen’s Health Systems. Her facility alone was looking for 40 to 60 extra nurses in critical care, telemetry, ER, med-surg and inpatient dialysis.

Like other states, Hawaii waived licensing requirements “to allow recent graduates to provide assistance in supporting roles such as screening and administrative work … to free up experienced and qualified nurses to focus on COVID-19 patients”.

“We need their support and work immediately,” Hawaii State Center for Nursing director Laura Reichhardt told the Star Advertiser.

The upside for nurses: increased demand, higher salaries

Let’s start with the good news, which is that the increased demand for travel nurses, even as it fluctuates from state to state over time, has driven up salaries.

Earlier this year, salaries for COVID-19 related travel nurse jobs soared to an average $3,000 a week, compared with an average $1,700/week travel nurse salary before. ICU and ER travel nurses saw the greatest opportunities, with compensation “surging to upwards of $4,000 per week”.

In Hawaii, Raethel said last month that a nurse could earn $4,800 a week — over 1.5 times as much as a regular nurse.

Research and advisory firm Staffing Industry Analysts expects “the travel nursing market to reach $6.4 billion in 2020, a 5% increase over last year’s revenue,” the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported. But beware: it’s such a booming business, it’s attracting some dodgy practices as well.

A new on-demand agency that billed itself “the New Uber of Healthcare Staffing” and touted “blockchain technology” was involved in a fiasco last month that left a group of travel nurses from around the country stranded in Florida, and sent home without pay without ever seeing a patient. They had been promised a guaranteed $6,000 working with COVID patients on “a very unique assignment” — but when they arrived they were given no work, left to cover their own costs, and ghosted by their agency contacts.

“People always feel they could have done more”

There are far more long-term, serious downsides too, however. Travel nursing can be incredibly fulfilling. But some of the very reasons why ever new travel nursing opportunities appear, as hospitals recruit new nurses to replace those who suffer burnout or have to stay at home because they tested positive, highlight the real risks involved.

For nurses like Janelle Orbon from Denver, rushing to the help of embattled colleagues in New York last March “was a no-brainer,” she told The Tablet: “That’s where I needed to be. I was fully trained and wanted to help and would have felt much worse not being there”.

“I was fully trained and wanted to help and would have felt much worse not being there”

Janelle Orbon

Many other nurses like her found a rewarding experience in being able to help when help was needed most. Ryan Cogdill, who went to Seattle, told CNN that he “felt a responsibility to be here,” not least so he could relieve exhausted colleagues who had been battling the virus since the start.

But the work of a crisis response nurse can be incredibly sobering too. “It’s been a humbling experience,” Stacey Phelps told us. An Alabama nurse who trekked up to New York City to fight COVID-19, she said the opportunity helped her to grow as a nurse but also cruelly confronted her with the limits of what she could do.

| “I have cried more in these past several weeks than I ever have in my entire nursing career. Sure I’ve lost patients before, but not like this. This is truly more than what I thought it would be when I left Alabama” — Read the moving and revealing testimony of Alabama nurse Stacey Phelps |

“I came to New York so naive. I came to help these patients with Covid along with all these warrior nurses. I was going to save lives. But that’s not the case here,” she wrote us, adding that “maybe God didn’t send me here to save lives. Maybe he sent me here to help keep [patients] comfortable and free of pain, to help families say goodbye, to give these other nurses time off to rest.”

Stacey shared how she had “cried more” than she had ever before in her nursing career, explaining that “I’ve lost patients before, but not like this.” She is not alone. “That stuff stays with you forever,” Mikki Sullivan told KOLD News 13 after working on COVID-19 units for months, “I was an emotional wreck when I got back”.

Carole Betteridge, a British former navy nurse who ran a field hospital in Afghanistan, sees “so many parallels,” pointing out that medical staff now face life-or-death situations “far more than we did in Iraq or Afghanistan”. The most visceral trigger of anxiety, she told The Guardian, was the feeling that even your best efforts had proven insufficient.

“People in hospitals will want to … save everybody, but sometimes that’s not possible, and it’s difficult to deal with,” she observed. “People always feel they could have done more.”

“Getting thrown into the fire is what we’re used to”

Studies after the SARS outbreak found that one in ten health workers developed PTSD, and trauma expert Prof. Neil Greenberg sees healthcare workers “at risk of high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder if they don’t get the right support”.

Yes, critical care nurses are highly resilient professionals who are used to having to cope with witnessing death and distress. As a travel nurse, Emily Cheng told CNN, “getting thrown into the fire is what we’re used to. I feel that we’re built for this.”

But, British psychologists argue, this crisis has new and specific risk factors — “including fear for staff’s own and their families’ health and the loss of informal support networks because of social distancing and working outside their usual teams.”

Those conditions apply in particular to travel nurses. And you hear it back in their stories.

Kristina Starcevic, who has been bouncing from job to job to tend to “the sickest of COVID-19 patients” told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that she enjoyed life as a traveler because it made her better rounded as a nurse, and not being local provided some relief: “I can switch out and you have a lighter heart”.

But Kristina also gave power of attorney to a close friend, because she has resigned herself to eventually getting infected: “It’s not if, but when.”

The responsibility of that risk weighed even more heavily on home health nurse Amanda Truog, interviewed by Modern Healthcare, who brings her husband and children along on her travel assignments.

It’s a freewheeling and trailblazing life, as her husband cares for the kids and manages his carpet-cleaning business from the road. But COVID-19 came to loom large when she got pregnant and tested positive right before her C-section. For two long weeks of quarantine, she agonized: “Is my baby going to die, my 2-year old, my husband?”

Having seen her brother fall ill with COVID-19, emergency department nurse Shanika Young was so afraid of infecting anyone, she told the Washington Post, she “went weeks without seeing her parents and newborn niece” and “adopted a hound-mix puppy to have a friend when she couldn’t see her own”.

The dangers you put yourself in, as crisis response nurse. The knowledge that you might endanger your family too — or the loneliness that comes with isolating yourself from your loved ones, even as you’re doing some of the hardest things you’ve ever done, in places that are new to you. The pain of your patients; the impossibility of caring for them safely; witnessing what one nurse called “death over Facetime” — helping dying patients say their online goodbyes to their families. It takes its toll.

“When you get an off day all you want to do is sleep, but dreams keep waking you,” Stacey Phelps wrote. “You try to hide the mental detritus this virus has left on your mind.”

Nurses “are not getting the support they need to feel safe on the job”

Many nurses like her are simply “not getting the support they need to feel safe on the job,” and now their mental as well as physical health is at serious risk. That’s the conclusion four associate and assistant professors in psychology and nursing from the University of Windsor drew.

Jody Ralph, Dana Ménard, Kendall Soucie, and Laurie Freeman interviewed nurses in the Canadian border city who work locally or commute across the US border to Detroit. They found that nurses suffered from sleep issues, nightmares and fatigue, and reported “increased alcohol consumption, unhealthy eating habits and use of sleep aids and cannabis” to get by.

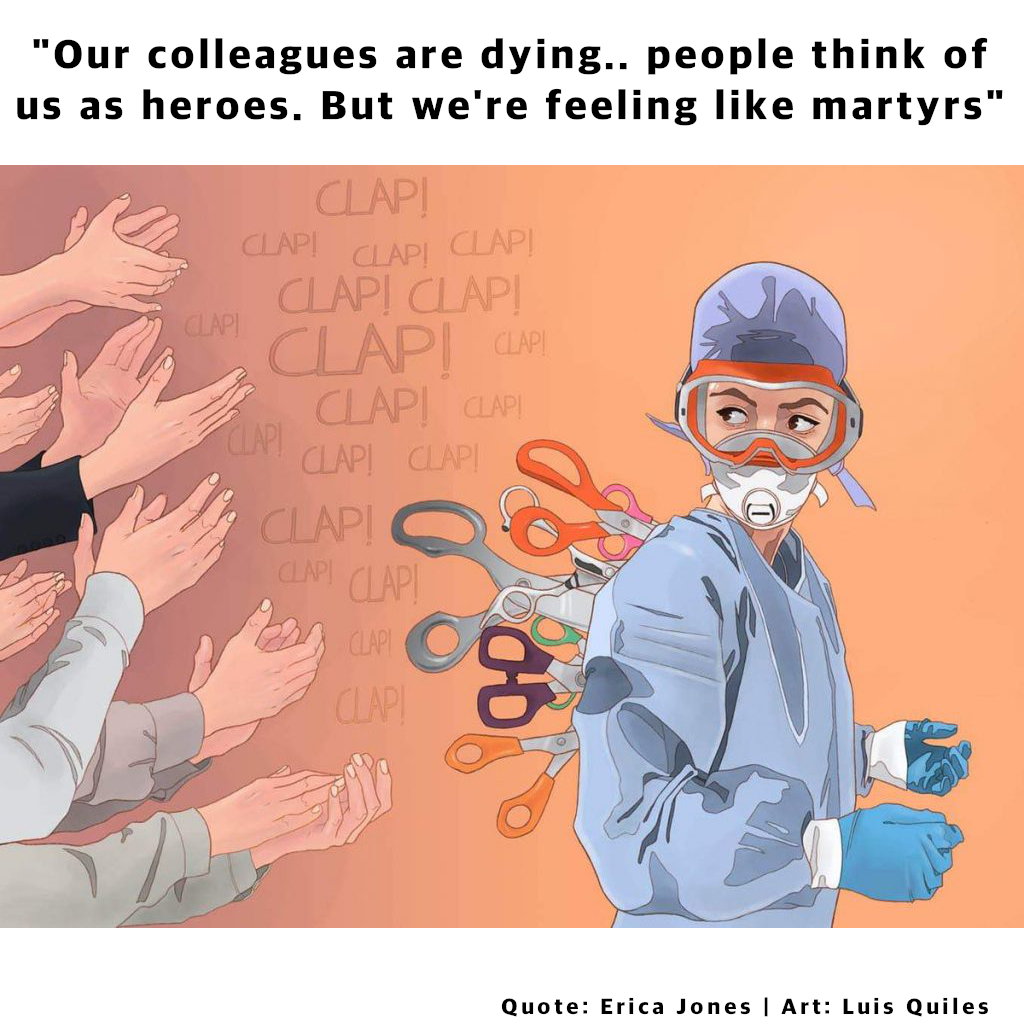

Their research confirms what healthcare workers have told reporters all year. Despite all the accolades, the Washington Post reported last June already, many doctors, nurses and EMTs are feeling lost and alone. “They second-guess their decisions, experience panic attacks, worry constantly about their patients, their families and themselves, and feel tremendous anxiety about how and when this might end.”

It’s unsustainable, the four researchers argued. Several nurses were “looking to a career change if the pandemic continues”. The SARS outbreak led to losses in the nursing workforce, which if repeated would “exacerbate” existing nurse shortages. (Even before the pandemic, turnover rates were frightening, with signs that two-thirds of millennial nurses are leaving the profession within five years.)

In short, if nurses are not better protected now, it will later bite employers in the back too. Effusive praise to “our health care heroes” won’t do; “we need solutions that go beyond a pat on the back” and “address unsafe working conditions and offer practical effective support”.

“It’s a question of how we care for our carers when the clapping stops”

What does that mean?

Military veterans who drew up guidelines for British nurses recommended a buddy system for experienced and inexperienced workers. They also suggested finding a way for a team which does difficult 12-hour shifts together to find a moment to decompress and reflect as well. “Talk about the good things and the things that didn’t go so well; discuss how you are dealing with things — and talk about your families and positive things,” Carole Betteridge suggested.

That makes some sense: nurses feel more comfortable seeking support from their “work family” than friends or family who aren’t nurses, the University of Windsor researchers found. But a major obstacle is fear of repercussions if employers find out you feel overwhelmed: “Heaven forbid, you say mental health or stress … because then they’ll take you from your unit, and say, put you at the front door as a greeter.”

If employers want their nurses to last, that kind of toxic culture has to change. But it’s not the only thing — and it’s the period after the immediate crisis subsides that really counts. “How well people are supported and how much stress they’re put under as they try to recover can make or break whether someone manages well or develops far more serious difficulties including PTSD,” says Prof. Greenberg.

Like other experts, he recommends far-reaching measures, which may sound utopian in the US labour market context. But maybe this is the time for change. Staff “should be treated like soldiers after tours — with time off and a gradual return to normal work,” he argues. Dr Julie Highfield recommends “an 18-month to two-year recovery period” with access to counselling and trauma-focused therapy.

“All healthcare workers should have the option of being assessed for conditions such as PTSD,” pleads Dr. Onkar Sahota. “It’s a question of how we care for our carers when the clapping stops.”

“How well people are supported and how much stress they’re put under as they try to recover can make or break whether someone manages well or develops far more serious difficulties including PTSD”

Prof. Neil Greenberg

In the meantime, it would help to limit how many hours on the front lines any one individual nurse can work. To rotate responsibilities to better distribute the burden. And to protect healthcare workers and ease their minds, “regular, convenient, and free” COVID-19 testing should always be available, as over 1,000 employees of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston pointed out in an open letter to hospital leadership after a coronavirus cluster emerged there and 33 staff members tested positive.

“We are literally putting our life on the line,” trauma nurse Trish Powers said, adding that “We shouldn’t have to fight to be tested.”

Finally, you’d think, at the very least employers could be expected to provide nurses with the PPE they need so they don’t have to fear for their own lives as well as those of their patients. What’s the hold-up there? We explained in another blog post: It’s all a matter of money and planning.

What do you think nurses need most — right now, and once

they’re off the Covid-19 shift? Tell us in the comments.

But let’s stop here to emphasize this. Not providing the support and equipment nurses need also sends a message, and it’s one that demoralizes the very people taking on some of the biggest burdens. “Not for the first time but certainly the strongest, I felt disposable to them — like my contributions and sacrifices don’t matter,” a Charleston, West-Virginia, nurse lamented after a local CEO added insult to injury by claiming that it was hospital staff bringing in the virus from home.

“We go into work every day knowing the risks we’ll need to take,” a colleague added. “Putting our families — our own children, sometimes — at risk. To say we’re to blame — how dare he? How dare he, when the conditions we’re working under make it nearly impossible to keep ourselves safe?”

Zane

Many states are asking for a $15/hr minimum wage, any RN, LPN, CNA working now should get extra $5/hr no matter what and double that if you haven’t had a vacation since March