It seems counterintuitive, and it’s really not how things should work: when a health emergency erupted in the United States, health workers started being furloughed and laid off en masse. How could that happen, and what can we expect next?

“All hands on deck,” they said. But weeks later, nurses started getting sent home

It was mid-March, and employers and agencies sounded the alarm. The Coronavirus pandemic had arrived, and they were going to need many more nurses — and soon. We said it too! “Whether clinically licensed or retired, our healthcare system needs your help!”, one nursing agency pleaded in a call to arms.

State officials sprang into action. They expedited licensing processes, issued temporary permits, suspended license expiration dates, waived application fees, eased screening processes. It was going to be all hands on deck. In Washington state alone, the nursing commission issued “an all-time high” of 3,857 temporary practice permits while “more than 600 nurses … volunteered to help fight COVID-19 from in and out of state”.

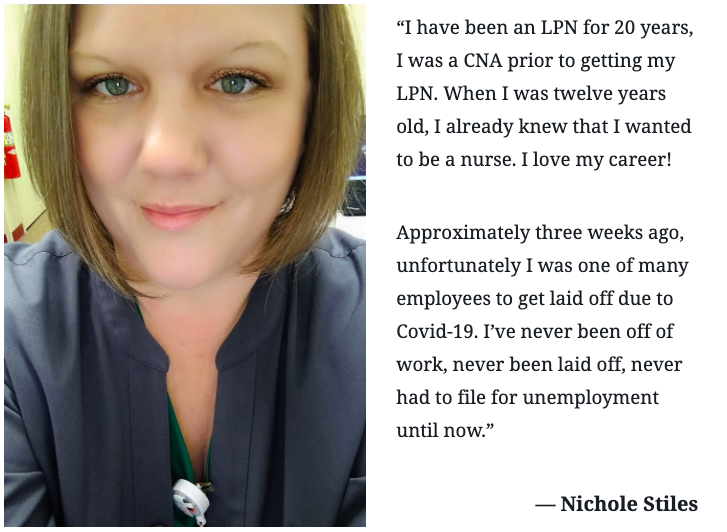

But that’s not quite how it turned out for many nurses. Even as tens of thousands of nurses made impossible, exhausting hours battling Covid-19 with inadequate PPE, other nurses suddenly faced a very different fate. They were being furloughed and laid off, and their numbers grew rapidly. We saw it in the comments sections to our Facebook posts too, where some of you started sounding off that your realities did not match our message that “everyone is needed”. People who had expected their skills to be essential were instead told they were no longer needed.

It was an alienating experience. “I feel we’re born to do this,” operating room nurse Paula Cunningham told CBS8. “We want to be caregivers, and when we’re not giving care, there’s an empty feeling, there’s a void.” Even if they could keep working, many nurses saw their hours or wages cut. Additional benefits like merit increases and tuition reimbursements were among the first to be suspended.

“We’re kind of jack-of-all-trades at this point”

As early as April 3, the New York Times reported that Oneida Health Hospital in upstate New York, for example, was “putting 25 percent to 30 percent of its employees on involuntary furlough”. Healthcare workers were being ordered to use their paid time off, and once those days ran out, take unpaid leave. A week later, the Washington Post reported that health systems like Bon Secours Mercy Health and Ballad Health were furloughing 700-1,300 employees each. Eventually, job losses in the healthcare sector grew to be “second only to those in the restaurant industry”.

It wasn’t necessarily like their work was no longer needed either. The frontline workers who were left to care for Covid-19 patients in dangerous conditions had to take more hours, even at reduced pay. “Some nurses still in the hospitals are taking on extra tasks in their already grueling 12-hour shifts,” NPR reported. They’re “mopping rooms, changing sheets, taking out the trash and arranging rides because the people who once did that are gone.”

One Bay Area nurse told NPR, “We’re kind of jack-of-all-trades at this point … We’re being phlebotomists, drawing labs. We’re being social workers. We’re being psychologists.” When a patient arrived at Palomar Health in San Diego County with broken bones, critical care trauma nurse Sue Phillips recounted, the doctor couldn’t turn to the orthopedic technicians, since those had been laid off. So “Phillips found herself putting traction on a hospital bed, a pulley system that slowly lifts and moves the broken body parts,” even though she had never had to do that before.

So how could this possibly happen? What could lead to the paradoxical situation that hundreds of thousands of healthcare workers were sent home in the middle of a pandemic, when they seemed more needed than ever?

“An absolute financial nightmare”

The Coronavirus emergency was a perfect storm, and hospitals were not prepared. The very way our healthcare system functions turned out to be ill-equipped for weathering a pandemic.

We’re not even talking about the inexcusable failure to stock enough PPE. We’re talking what one hospital administrator called “an absolute financial nightmare”. Healthcare companies large and small started bleeding money as revenues plummeted and expenses soared.

| “I came to New York so naive. I came to help these patients with Covid along with all these warrior nurses. I was going to make a difference. I was going to save lives.” — Read the moving and revealing testimony of Alabama nurse Stacey Phelps |

Michigan’s Beaumont hospital system for example, the Washington Post reported, normally “earns about $16 million each month in net operating income,” but suddenly it was “losing about $100 million a month”. Nationally, the American Hospital Association estimated that “individual hospitals are losing as much as $1 million per day”.

The problem soon became existential especially for rural hospitals and for smaller practices and clinics, many of whom “were living on a financial edge to start with,” as Dr. Gary Price of the Physicians Foundation had noted. In less than two months, revenue at private practices in California “dropped by an average of 64%”. The spokeswoman of Mad River Community Hospital in California’s rural Humboldt County, which lost 50% of its revenue, despaired that at “a profit margin of 2% to 3% … it is devastating”.

When hospitals were more needed than ever, they started bleeding money. How does that work?

It seems counterintuitive. How can a pandemic mean fewer patients and less revenue? Let’s quickly list the reasons why.

Elective surgeries and services were cancelled or deferred. In dozens of states, governors issued executive orders or guidelines that banned or limited non-essential procedures. Surgeon general Dr. Jerome Adams “implored hospitals to halt elective procedures”.

So how could this happen? What could lead to the paradoxical situation that hundreds of thousands of healthcare workers were sent home in the middle of a pandemic, when they were more needed than ever?

Hospitals hurried to empty beds to create space for the Covid-19 patients they expected, and to redesign their facilities to separate them from other patients. Children’s Hospital in St. Paul, MN, for example, “basically [shut] down everything except the emergency department and the intensive care unit”.

Even when people still had to come in for non-Covid reasons, hospitals and individual healthcare workers were “finding ways to get them home as fast as possible” to reduce the risk. And patients themselves soon started staying away altogether, putting off checkups and elective procedures. Even those needing serious emergency care were wary of coming in.

Ambulatory healthcare services like those of family physicians were especially affected. One larger New York practice went “from seeing about 250 patients each day to just five” because patients stayed home and physicians preferred to avoid the risk: “it’s not the right thing to do to bring people in with chronic disease and having them exposed to us and us exposed to them”.

Physicians switched to practicing tele-medicine, but that brings in less revenue than in-patient visits. Meanwhile, hospitals still had to keep the lights on. They could furlough many of their employees, but other costs remained.

Preparing for Covid-19 patients, they faced major additional expenses too. Hospitals had to invest in ventilators, laboratory testing, PPE, drive-by testing sites, and negative air pressure rooms to isolate infected patients. They had to contend with price gouging too, with masks that normally cost 50 cents going up to $6 each when supplies ran low.

Trying to find solutions

To avoid laying off nurses, many employers tried redeploying them first. But the increasing specialization of the nursing profession limited what could be done. “Moving nurses from one workplace setting to another is not as simple as it sounds, because nurses tend to specialize or stay in one care setting,” the Washington Center for Nursing’s Sofia Aragon explained.

Janet Conway of Cape Fear Valley Health System in North Carolina used the specialized training of many of its operating room nurses as an example. “Those O.R. nurses, many have never worked as a floor nurse”.

To their credit, when crunch time came executives at some companies took larger pay cuts themselves too. CEO Andrea Walsh of Minnesota’s HealthPartners, which expected to furlough its staff by 10%, reduced her salary by 40%, and that of other leaders by up to 30%. At Michigan Medicine, which furloughed or laid off 1,400 employees, CEO Marschall Runge took a 20% pay cut.

Some nurse groups, in their turn, started helping their members get through the hardest times. The Emergency Nurses Association, for example, created a relief fund for ER nurses who are struggling financially.

In March, the federal government moved in to help in a big way. The stimulus package Congress approved that month included $100 billion in emergency funding for hospitals and other health providers. $10 billion of that was specifically allocated for rural hospitals.

Keep in mind, however, that this wasn’t just supposed to offset lost income, but the costs of Covid-19 care equipment and supplies, not to mention building and retrofitting temporary facilities, as well. $100 billion sounds like a lot, but the Advisory Board consulting firm pointed out that it just about equalled total hospital industry revenue in a single month. The UW Medicine health care system in Washington, for example, “secured some $180 million in federal and state relief funds” but still faces “a $500 million budget shortfall by summer’s end”.

Structural problems: our healthcare system is ill-equipped for a pandemic

Hospitals expected a surge of Covid-19 patients. In all too many places it soon materialized, and dangerously ill patients filled up hallways and field hospitals. But far more other patients disappeared and, as the LA Times observed, “American healthcare is a business, and the economics are simple: Fewer patients means less money.”

It wasn’t even just about fewer patients though. The contradiction of healthcare facilities suffering plummeting revenues in the middle of a pandemic also reflects other issues in our healthcare system, where not all patients are created equal.

“The only people who are coming into the hospitals are COVID-19 patients and emergencies,” the American Hospital Association’s Tom Nickels told NPR in early May. “All of the so-called elective surgery, hips and knees and cardiac, etcetera,” were no longer being done. And those are much more profitable. When the association predicted $200 billion losses within four months for U.S. hospitals and health systems, $160 billion of that was about “lost revenue from more lucrative elective procedures”.

Our two-tier system where some patients have private health insurance and others rely on state or federal programs (or aren’t insured at all) has a similar effect, and this is likely to extend the impact of the current crisis. The millions of newly unemployed have also lost their employer-sponsored health insurance, which “could leave hospitals taking on more patients who are unable to pay” at all. Alternatively, they will be covered by Medicaid, Medicare or state programs like Medi-Cal, which reimburse healthcare providers at much lower rates than private plans. As USC health economist Glenn Melnick explained to the LA Times, this means that “even where volume goes back to where it was, […] I’m going to get a lot less money for the same service.”

“This crisis is an opportunity to rethink how the American hospital system is funded.”

Randi Weingarten

Randi Weingarten, whose AFT union includes the National Federation of Nurses, looked at all this and concluded that “this crisis is an opportunity to rethink how the American hospital system is funded.” In a business-oriented system like ours, hospitals stand or fall on revenues even during a pandemic, but this “is not an issue in Canada. It’s not an issue in Great Britain”’.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

As April turned to May, ominous warnings abounded over the post-pandemic future of health care. “This pandemic is going to change everything,” said Minnesota Hospital Association president Dr. Rahul Koranne.

After 35 years of healthy job prospects, Glenn Melnick warned, “it’s going to have to slow down” as employers face lower revenue “in a permanent way.” It’s not as simple as work coming back online when patients catch up with elective surgeries, he explained. The millions of people who lost their health insurance along with their jobs “may continue to avoid or put off medical care”.

But the U.S. economic downturn seemed to be leveling off from early May on, and by late May reports started emerging of healthcare employers “starting to bring furloughed workers back as they resume nonemergency procedures”. In Florida, for example, Sarasota Memorial Hospital “brought back about 200 employees, including nurses, who were furloughed in April.”

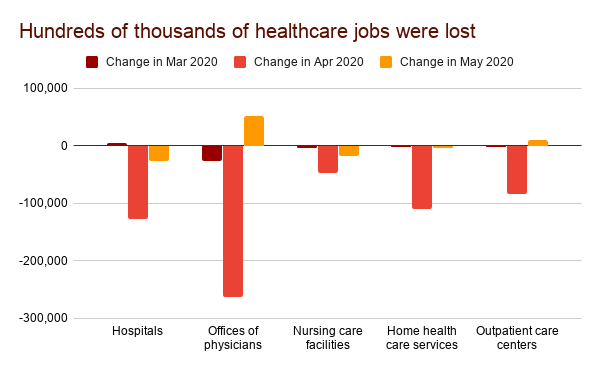

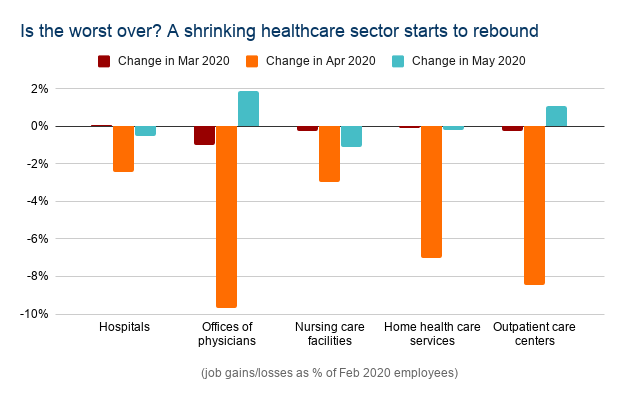

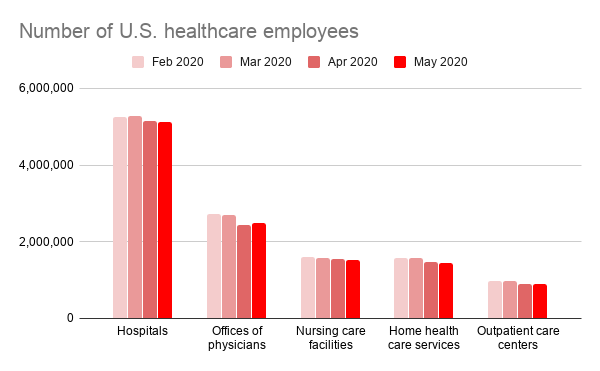

The monthly jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics last Friday put some (large) numbers to that emerging recovery. Overall, the healthcare sector added 312 thousand jobs in May, after losing 1.5 million in April.

The places that had been hit most heavily were also the ones that started bouncing back now. Offices of physicians, where 263 thousand jobs were lost in April, saw 51 thousand of them return in May. Outpatient care centers saw 11 thousand jobs return in May, where 83 thousand were lost in April.

Employment in these workplaces and in home health care is still down 7-9% from February, though. On the other hand, hospitals and nursing care facilities kept losing jobs in April, if a lot less quickly, and there are now 149 thousand fewer hospital employees than three months ago. But employment in those sectors is still the safer bet: the total number of hospital and nursing care employees is down by just 3-4% from February.

We can help!

This is where we would like to also remind you of the services we provide. If you were laid off or furloughed this Spring, the situation will have seemed scary these past months — but it is definitely still worth looking. Especially now, when positions might open up again. Even now, there are still over 5 million hospital jobs, a large many of them for RNs, LPNs and CNAs. Things are in flux, and change means turnover: employers are filling positions they eliminated earlier, and the same nurses might no longer be available.

The longer you are away from the job, the more you will worry about being able to come back, so it’s best to start looking now. Of course we can’t promise that everyone who registers on our website will secure a new job. But we can promise one of the easiest, most user-friendly tools around to find a position — specifically in your field, for someone with your experience and your qualifications — as soon as it appears.

Once that job opens up, you want the employer or recruiter who is advertising it to see your name. We can help with that. Register on our website if you haven’t done so yet. If you already registered: update your profile! Our website works much like other professional networking sites and job boards — when you don’t keep your profile up to date, you become less visible to the employers who are looking for new nurses. So don’t drift out of sight. Add your latest qualifications. Update your work experience. Make sure to let them know how far you’ve come!

Whether you are anxious to jump back in, or eager to move on to another job after experiences in the last few months, we provide a quick and effective way to check what is available right now, and to keep tabs on new opportunities as they appear. It’s been a tough year so far, to say the least … and you deserve to catch a break!

Alexandria DiNome

Hi, I’ve been a ED and ICU RN for 40 plus years and I thought at 67 I should retire but after one month, I was looking for work! I found a great job 2 days a week in a a Transfer Center getting patients where there needed to go and getting the physicians on the phone they needed to consult with….perfect job as I also years ago did a Tele heath job called “Ask a Nurse” and I really wanted to stay working contributing to my community but I felt patient care was getting getting difficult for me. Covid hit and I’m retired/furloughed for 30-60 days……..I’m a patient girl hopefully this job will call me back!