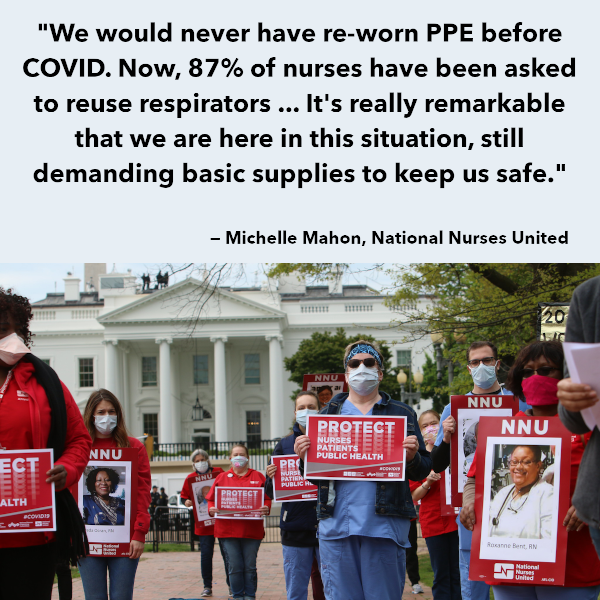

It’s the issue that just doesn’t seem to go away. Even now, from coast to coast, too many nurses have to improvise with unsafe equipment. Reusing masks and face shields. Storing N95s in paper bags.

Even where there is now enough PPE, worries are mounting that there will still not be enough if there is a new surge this fall.

After over half a year, how can that possibly be? It’s all a matter of money, planning, and a changing economy.

Fined by OSHA! But will they care?

Two weeks ago, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) fined three hospital systems for failing to protect their employees with proper PPE, Healthcare Dive reported. It imposed some of the highest possible fines it can levy. But the overwhelming majority of OSHA cases go nowhere. “Of the more than 4,500 complaints OSHA has received about COVID-19-related working conditions in the medical industry,” ProPublica reported in early August, it “closed nearly 3,200”.

It’s also doubtful whether the fines will make an impression. Hackensack Meridian Health, which was fined $28,070 for not providing its home healthcare employees with appropriately fitting respirator masks, “posted a profit of $676.9 million last year,” Healthcare Dive pointed out.

In fact, “all of the nation’s largest for-profit hospital chains saw higher profits” in the second quarter of this year, even as the Coronavirus crisis shut down many elective surgeries. Some even tripled their net income year-on-year, thanks to federal relief funds which critics like Robert Berenson say were rushed out in such haste that most of the money went to wealthier systems “that didn’t need the money”.

“Why is the world’s richest country still struggling to meet the demand for an item that once cost around $1 apiece?”

So it’s not lack of money that has stopped employers from providing nurses with PPE. Then what is it? Last week, Washington Post journalist Jessica Contrera asked the same, baffled question: six months in, how on earth “is the world’s richest country still struggling to meet the demand for an item that once cost around $1 a piece?”

John Hopkins Hospital was one of the few employers that had built up a stockpile of its own PPE, Contrera reported, and even there “nurses are asked to keep wearing their N95s until the masks are broken or visibly dirty”. Elsewhere, hospital administrators preferred to buy only as much as they needed in the short term, to save money on storage costs and replacing expired stock.

That story has been told before. In recent years, healthcare companies switched to just-in-time supply chains, at the same time as PPE production mostly moved offshore to low-cost Asian countries — 80% of the world’s masks are now made in China. Then the pandemic broke out and borders closed, PPE imports screeched to a halt, and hospitals were left without.

They might have expected that the government had emergency back-up supplies. It used to. Federal “warehouses in secret locations” were filled with PPE for just such a disaster scenario, Contrera observes. But almost all those supplies were depleted in 2009 during the H1N1 flu epidemic. And despite dire warnings in “alarming reports” that kept appearing almost every year since, they were never replenished.

The government “did fund the invention of a “one-of-a-kind, high-speed machine” that could make 1.5 million N95s per day,” she adds, “but when the design was completed in 2018, the Trump administration did not purchase it”. Then they “turned down a January offer from a manufacturer who could make millions of N95s” and waited two more months.

So by March, even John Hopkins had volunteers making face shields by hand, with scissors, staplers and glue guns.

“We’ve been re-using PPE since day one!”

The numbers should look better now. According to the government, 160 million N95s will soon be produced in the US every month, and the Strategic National Stockpile has 60 million N95s on hand again. Over in Aberdeen, South Dakota, hundreds of new employees at a 3M factory are manning production lines 24/7.

But it has not been enough. In a survey this August, the American Nurses Association didn’t just find that two-thirds of nurses were still required to reuse respirators — and half had to do so for more than five days. It found that both numbers had actually gone up since May!

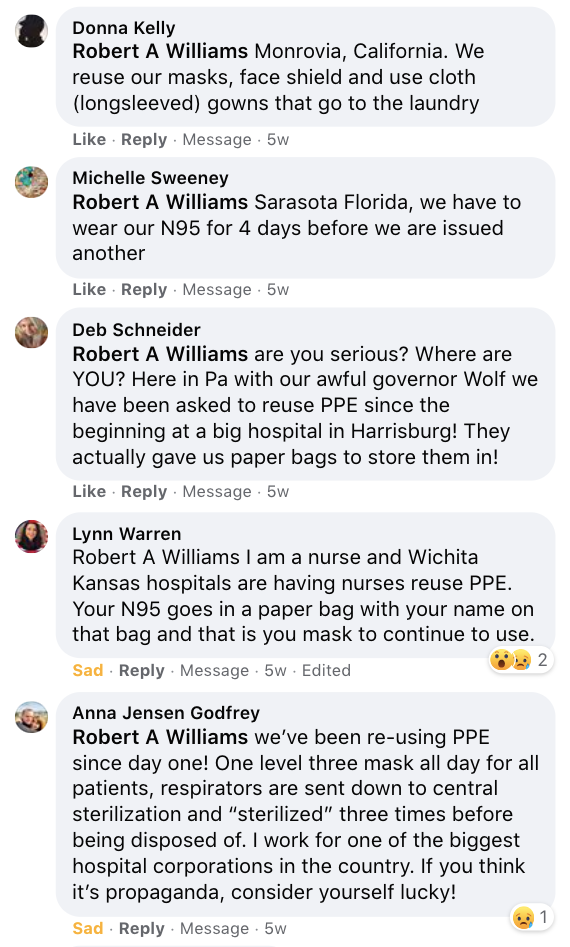

Almost all the nurses in our comments section told the same story. “We’ve been re-using PPE since day one!,” one nurse exclaimed when a single dissenter called talk of shortages “propaganda”.

In the Chicago Sun-Times, Brett Chase reported this week that striking nurses at University of Illinois Hospital had successfully made ramping up supplies of PPE a key demand. But local hospitals were cautious about how long their current supplies would last in case of a second wave.

“The question becomes how big a surge and for how long?,” said Eric Tritch, vice president of supply chain at the University of Chicago hospital.

Like Tritch, the University of Illinois Hospital’s acting chief quality officer Dr. Susan Bleasdale emphasized to the reporter that they have been preparing for a surge. But the hospital is “inhibited” from significantly stockpiling, she added, “until there is significant improvement in the national supply chain.”

“It is not profitable to make respirators in the United States”

The simple underlying problem, Peter Tsai pointed out to the Post‘s Jessica Contrera, is that “it is not profitable to make respirators in the United States”.

The scientist and inventor of N95 filter media explained that it “can take six months just to create one manufacturing line that makes the N95′s filter,” and only 15-20 companies could potentially produce them more quickly. But they are reluctant because of the cost, and they need know-how.

Two things would help, Contrera explains. The government could provide guarantees, or use the Defense Production Act (DPA) to make the investment itself. Industry organizations and unions alike — AMA, AHA, ANA — see this as the solution, but the administration has only done so in piecemeal ways. It spent $3 billion in DPA contracts to produce ventilators when a shortage of those seemed to loom, the “vast majority” of which are going unused, but only a tenth of that on N95 supply chains.

Second, manufacturers could share plans and designs, like they did with ventilators. The DPA could be used to protect them from antitrust laws. But it’s not happening. Even as 3M spokeswoman Jennifer Ehrlich acknowledged that “the demand is more than we, and the entire industry, can supply for the foreseeable future,” the company and its counterparts jealously guard their intellectual property.

As a result, companies that started trying to make more N95s were “figuring out the process from scratch” and wasted time with designs that didn’t work or weren’t safe.

In the meantime, too many nurses still wait for the basic tools to keep themselves and their patients safe, reusing masks even when doing so means living with fear, every day. “I wore the same mask literally for 30 days,” a Veterans Affairs home health care nurse told Brett Chase.

In line behind them, lest we forget, are all the other essential workers who are in close proximity to strangers all day, who would benefit from better masks as well. Too many of them are falling ill, too, or worse — at an enormous human cost, and a significant economic one too.

“Here we are, at nearly 200k deaths,” Jessica Contrera tweeted after finishing her story, “and we’re still struggling to get N95s” to the healthcare professionals we praise as “heroes”. And “as long as the shortage exists for healthcare, everyone else who could be protected by these respirators (grocery clerks, flight attendants, teachers) … aren’t”.