National Public Radio conducted an impressively in-depth, four-part report about the working conditions and health risks of nurses, full of worrying statistical data and heartbreaking personal stories.

The short of it: “nursing employees suffer more debilitating back and other injuries than almost any other occupation — and they get those injuries mainly from doing the everyday tasks of lifting and moving patients”. Nurses and especially nursing assistants face physical pressures at work that are as dangerous as those experienced by factory workers or truck drivers, but lack many of the same safety tools, restrictions and procedures. The result:

According to surveys by the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), there are more than 35,000 back and other injuries among nursing employees every year, severe enough that they have to miss work. Nursing assistants and orderlies each suffer roughly three times the rate of back and other musculoskeletal injuries as construction laborers.

We summarize the NPR stories, which add up to a whopping 10,000+ words, into about a quarter that size, illustrate them with a couple of additional charts of our own, follow up on a lead or two, and take note of how this NPR report hasn’t been the only recent story to raise the health and safety of nurses.

The good news? Adequate equipment and training could “dramatically reduce” those back injury rates. It would require a significant financial investment and consistent commitment on the part of hospital administrators – but those would pay themselves back in the longer run, even in a purely financial sense. The NPR report itself has attracted ample attention in the industry, which will hopefully help increase the pressure on employers to make protecting nurses a long-overdue priority, and act.

|

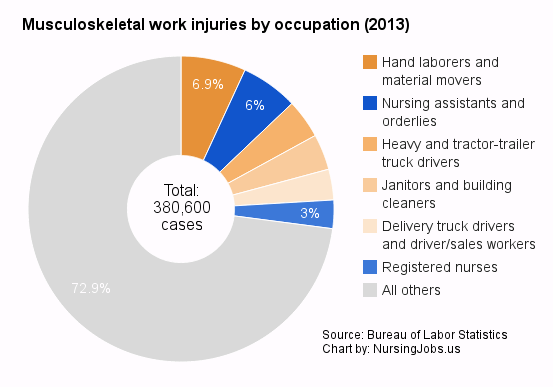

Close to 10% of all musculoskeletal injuriesThe NPR reports include a great chart showing musculoskeletal injury rates for nursing assistants, orderlies, registered nurses and personal care aides in comparison with some occupations that are traditionally seen as involving, well, backbreaking work, such as firefighters and construction laborers. But we’d like to add two charts to give an indication of the total numbers involved. 1. More nursing assistants suffer this kind of back injuries at their work than any single other occupation identified by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, including warehouse workers and heavy truck drivers. Registered nurses come in fifth place. 2. Of all the musculoskeletal injuries suffered at the workplace, registered nurses, nursing assistants and orderlies together account for close to 10%. |

1. “Hospitals Fail To Protect Nursing Staff From Becoming Patients”

Just how heavy a workload – literally – do those in the nursing professions face? NPR’s first, extensive report tells the story:

[In the early 1990s,] federal researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) started studying why so many nursing staff were hurting their backs. They were stunned by what they learned. James Collins [..] says, before studying back injuries among nursing employees, he focused on auto factory workers. His subjects were “93 percent men, heavily tattooed, macho workforce, Harley-Davidson rider type guys,” he says. “And they were prohibited from lifting over 35 pounds through the course of their work.” Nursing employees in a typical hospital lift far heavier patients a dozen or more times every day. “That was my biggest shock and surprise,” Collins says. “And the big deal is, the injuries are so severe that for many people, they’re career-ending.”

Moreover, the so-called “proper body mechanics” don’t work:

Studies by university and government researchers began to show decades ago that the traditional way hospitals and nursing schools teach staff to move patients — bend your knees and keep your back straight, using “proper body mechanics” — is dangerous. “The bottom line is, there’s no safe way to lift a patient manually,” says William Marras, director of The Ohio State University’s Spine Research Institute [..].

And most hospitals are reluctant – far too reluctant – to act:

Some hospitals [..] report that they have reduced lifting injuries among nursing staff by up to 80 percent — using an approach often called “safe patient handling.” They use special machinery to lift patients, similar to motorized hoists that factory workers use to move heavy parts. [..] Yet the majority of the nation’s hospitals have not taken similar action. [..]. “Too many hospital administrators see nursing staff as second-class citizens,” says Suzanne Gordon, author of Nursing Against the Odds.

Legislative will is lacking too, assistant secretary of Labor David Michaels explained. He heads the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and says the issue is very important because “it means that workers who are relatively young have to stop working early, in many cases.” But OSHA’s powers “have been so limited by Congress and court decisions that the agency can do little to require hospitals to protect nursing employees”.

Surging obesity rates are making things worse, one registered nurse in the story explains: “A 250- to 300-pound patient can be very common in our unit. And to even be able to lift their leg is probably 60, 70 pounds maybe”. The changing nature of hospital policies have contributed as well: “most patients staying in hospitals today are sicker than the patients of 20 years ago. Hospitals are treating as many people as they can in outpatient clinics, saving inpatient beds for those who most need round-the-clock care. But no matter how sick or heavy they are, there’s a push to get them out of bed as soon as possible and moving — even if the patients can’t even swing themselves to the edge of the bed.”

This first installment of the NPR reportage also included a case study about a Kaiser Permanente hospital in Walnut Creek, California. Interviews and rare access to internal documents showed how day-to-day practice is a far cry from official standards, and there is no reason to believe that the hospital was an exception. When the nurses would urgently request a lift team, they would learn that the team members had been reassigned to other duties, and newly purchased patient lifting equipment was often blocked or inaccessible. Since California is one of ten states with an effective safe patient handling law, however, nursing employees were able to pursue a complaint with the state, and a judge ordered the hospital to fix the problems.

|

It’s not just about having your back: Other health risks

Solutions Just like the NPR series was to reveal long-term solutions for the outsized rate of back injuries among registered nurses and nursing assistants, there are ways to tackle these issues too, both for institutions and nurses themselves. Several states have adopted laws to better protect nurses against workplace violence, the Safety + Health piece documented. The Department of Labor presented Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence. The American Nurses Association provides a free “HealthyNurse” risk appraisal [UPDATE: now transformed into the Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation Grand Challenge!], which nurses can use to check what health, safety and wellness risks they are experiencing compared against ideal standards and national averages. For those who feel they might suffer from depression but are reluctant to immediately seek professional treatment, researcher Susan Letvak suggests, as first step, to use a free online tool like MoodGYM or the PHQ Screener. Letvak herself last year introduced seven practical articles in the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing which offer “specific measures about how nurses can maintain and improve their physical and emotional health”. |

2. Even ‘Proper’ Technique Exposes Nurses’ Spines To Dangerous Forces

The nut graph of the second installment of NPR’s reportage is as simple as it is blunt:

[N]ursing schools and hospitals [..] keep teaching nursing employees how to lift and move patients in ways that could inadvertently result in career-ending back injuries.

For over a century, nurses are being taught that the right way to lift patients is by using “proper body mechanics”: keep your back straight and bend at the knees and hips. But that’s exactly how Sunny Vespico, a registered nurse in Philadelphia, herniated one of her discs when she was working a night shift in the intensive care unit and tried to lift a 200-pound patient with a colleague. “I am 36 years old,” she now says: “I’ve had three surgeries over the last two years.” The report quotes William Marras, director of the Spine Research Institute at Ohio State University:

Hospital staff can lift and move patients safely only if they stop doing it manually — with their own human strength — and use machines and other equipment instead, Marras says. That means nursing staff might move patients by using technology such as a ceiling hoist — much like factory workers move heavy parts.

There’s just “no safe way to do it with body mechanics,” he says. That’s all the more true when “about 70 percent of the adult population is overweight or obese [..] and many patients in acute care hospitals top 300 pounds”. The reporter highlights some key findings from the institute’s decade and a half of experiments. The way nursing employees tend to have to bend over the patients when lifting them, for example, imposes forces on their spine “much, much higher than what you’d expect in an assembly line worker,” causing microscopic tears in their end plates. When they eventually suffer an injury, it’s often just the straw that broke the camel’s back. Working with “teams of two to four dedicated lifters,” as some hospitals do, is no solution either:

[T]eam lifting reduces the amount of weight each person has to handle, and it can reduce “compression” forces on their spines [..]. But Marras’ studies show that even teams don’t reduce those compression forces to safe levels. Worse: The studies show that lifting patients in teams actually increases another kind of force — shear. [..] “The problem is, our tolerances to that shear are nowhere near as great as they would be to compression,” says Marras. “And so we’re at greater risk when we’re lifting as a team.

The bottom line, he says, is that “there’s no safe way to lift a patient manually”. But hospitals remain reluctant to face these findings. One hospital’s vice president of acute care services, contacted by the reporter, proudly referred to “proper body mechanics”. Only some rooms in her hospital had motorized lifts. Why? “Money and space constraints”.

|

Applying for a job in nursing?There may not be any safe way to lift or move patients with “proper body mechanics,” but that doesn’t stop many hospitals from recommending the practice and requiring it from future employees. Hospitals and medical centers from Jackson, MS to Wallingford, CT and Clermont, FL are posting job advertisements for nursing assistants or physical therapists in which they include using “proper body mechanics” as essential required skill. Something to keep an eye on when you’re looking for your next nursing job. |

3. Hospital To Nurses: Your Injuries Are Not Our Problem

Sometimes, the letter of the law is clear. In North Carolina, the third part of NPR’s reporting explains:

State laws require companies to cover employees’ medical bills when they are injured doing their jobs. Companies also have to pay workers’ compensation to support injured employees while they’re missing work — and missing their paychecks.

In practice, when a nurse gets injured, it often doesn’t quite work out this way. Things can take a heartbreakingly different turn, as the story of Terry Cawthorn, a former nurse at Mission Hospital in Asheville, shows. She had worked there for over 20 years, and says: “nursing’s not just a job. It’s who you are.” But when she suffered back injuries at work and ended up needing a “lumbar interbody fusion,” with the surgeon building a metal cage around her spine, the hospital cut her loose. Court documents show that the hospital’s own medical staff concluded that she was hurt moving patients, but administrators responded with denial and deception. They served her with the notification that she was fired while she was still in the hospital, two days after surgery.

It wasn’t an exception either. Joshua Klaaren, who worked at Mission’s staff health clinic for six years, recounts in the report that it was “very, very, very common” to see nurses and nurses’ assistants who hurt their back managing, moving and lifting patients, but they were ordered not to record their observations:

Klaaren and other medical specialists from Mission’s staff clinic — who talked only on condition that we withhold their names, for fear of retaliation — told NPR that whenever they examined injured employees, they were required to fill out a form [..] with two boxes: “In our opinion, injury or illness is” or “is not work related.” Hospital officials ordered the occupational health staff not to check either box, Klaaren and other sources told NPR. Instead, hospital administrators filled them out — even if they had not seen the injured employee.

Worse:

The doctor who ran the staff health clinic, J. Paul Martin, warned Mission’s executives for years that the hospital was mistreating injured employees, according to dozens of internal hospital emails and other documents obtained by NPR. The doctor’s emails went to Mission’s vice president and general counsel, the chief of staff, a member of the board of directors, and others. [Martin] wrote: “I cannot stand by and watch our employees treated that way.” Hospital executives told Martin, in effect, that these issues were not his concern, according to the documents.

The hospital’s practices were so bad that the state’s courts “ruled repeatedly [..] that Mission Hospital refused to help injured nurses and others despite clear evidence that they got hurt on the job”. In 2002, the court ruled that Mission’s refusal to cover medical costs was “based upon stubborn, unfounded litigiousness,” and in 2004 it deemed hospital officials to have “acted in bad faith” by not sharing evidence. In 2012, “judges on the workers’ compensation court got so upset [..] that they said Mission should be investigated for fraud.” But, the report states, “Mission is not unique. NPR found similar attitudes toward nurses in hospitals around the country”.

Exactly how widespread those practices are is impossible to tell: “hospitals are not generally required to make their injury statistics public, so it’s difficult to compare them”. But NPR did find that most hospitals have failed to tackle the problem even as “studies by the U.S. government and university researchers” have showed “that hospitals can prevent many of those injuries, if hospital administrators invest enough time and money”. The motivation, whether it’s about refusing injured employees the support they deserve or investing in the equipment to keep them safe, is the same. “The view is, for every dollar I prevent going to a worker, that’s more dollars for the company” to spend elsewhere in the hospital, says former judge Douglas Berger.

A research manager at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health told the reporter that safety and health officers tell him protecting nurses just never seems to be enough of a priority:

Collins says safety directors tell him, ” ‘Just when I think I’ve got the CEO sold that we need [to spend] the funds for this comprehensive safe patient lifting program, in comes the chief of surgery describing the latest laser to improve his surgical outcomes.’ ” Collins says the surgeons inevitably get the money — which is often good news for patients — but the proposal to protect nursing employees goes “back at the end of the line.”

“Historically,” Suzanne Gordon tells the reporter, “hospital administrators viewed nurses as a disposable labor force”. Terry Cawthorn says that “I really thought that I was someone to Mission [..]. I had poured my life into nursing. And when I got hurt, I meant nothing. I was absolutely nothing to the hospital.” The hospital has a new CEO now, who says he changed course when he came in and an outside consultant has given them “a glowing report” about how they have handled workers’ compensation cases since . But when NPR asked for a copy, the request was denied: “This report is for internal use only and is not provided to third parties.”

|

Mission accomplished?From December 2004 to January 2010, Joe Damore was the CEO of Mission Health (which runs five smaller hospitals as well as Mission Hospital). He was paid over $800,000 in salary and benefits in 2007, a local blogger noted; in 2009 it was $1,006,712. The COO, Brian Aston, CFO Charles F. Ayscue, and Chief Medical Officer Dale Fell each received over $500,000 in salary and benefits. George Renfro, the chairman of Mission’s board, said at the time of Damore’s resignation that tensions between physicians and the administration had been “one issue leading to the resignation,” elaborating that “there were issues that would require lots of change in management and management style”. He added that “we were stymied by lots of issues and questions that had to be resolved, and [..] as we talked to Joe, it became apparent that the best answer to those issues was that he resign.” The resignation followed a period during which over a dozen local medical practices sent a joint letter expressing concerns about the hospital’s direction, and a committee investigating relations between doctors and hospital administration presented 14 recommendations aimed at giving doctors and employees a greater voice. Damore is now Vice President of the Population Health team of Premier Inc, a “healthcare performance improvement alliance”. Aston, who is is now a senior partner at an executive search firm, left Mission in 2011, as did Mission’s human resources director, Maria Roloff, who retired. Ron Paulus became Mission’s new CEO in August 2010, which was still two years before the judges on the workers’ compensation court said Mission should be investigated for fraud. In 2012, Paulus received $1.8 million in salary and benefits, and COO Jill Hoggard Green and CFO Charles F. Ayscue both over $750,000. Price increases at Mission Health have been lower than elsewhere, leading to costs that are $1,000 less per admission than in similar hospitals, but this year it will have to cut costs by $42 million and the reorganization could mean layoffs, the Asheville Citizen-Times reported. Mission Health expects gross revenues of $1.5 billion in 2015, but an operating margin of just 1.7%, which Hoggard Green said would not cover raises, new equipment or new buildings. In a video message to employees, Paulus added that freezing raises would not suffice, and he told them there had already been deep salary cuts for hospital executives. Therefore “the company is looking at everything from services and procedures to staffing levels to billing and payment collections across all its locations, including its five rural hospitals”. In line with national trends, Mission will invest more in community health centers and out-patient providers, however. |

4. At VA Hospitals, Training And Technology Reduce Nurses’ Injuries

The final installment of NPR’s initial four-part report showed how different things can be. How adequate equipment and training can “dramatically reduce” injury rates. But it requires a significant financial investment; consistent commitment from hospital administrators – and intense (re)training of nurses. Still it pays off in the long run, even in purely financial terms: it eliminates significant costs in treating injured nurses, hiring replacement nurses, and productivity losses as a result of injuries.

Leading the way? The VA — the Department of Veterans Affairs. The reporter spoke with Tony Hilton, the safe patient handling and mobility coordinator at a VA hospital in Loma Linda, California. “Nobody at this VA, she said, is allowed to move patients the traditional way anymore. “The guideline is, you’re not manually moving or handling patients. You’re using technology.””

Already back in the 1990s, a top researcher at the VA is quoted, “everybody knew” about the problem:

VA records showed that more than 2,400 of its nursing staff suffered debilitating injuries every year from lifting patients. [..] The VA’s own studies estimated that its hospitals were spending at least $22 million every year treating back and other injuries among nursing staff. And that figure “likely represents a substantial underestimate” [..].

So the agency responded with a sweeping program to “transform all of its 153 hospitals”. It declared a patient body weight of 35 pounds “the maximum weight [for] lifting and moving patients” and spent over $200 million on a “safe patient handling program.” In Loma Linda, the reporter could see the results:

- Ceiling lifts everywhere. Not just in the ICU and some surgery rooms, like in some private hospitals, but in all the hospital’s 207 patient rooms, and in imaging departments, clinics and the dialysis center too. Cost: $2 million.

- HoverMatt floating mattresses, which mean “workers don’t have to lift a patient from a bed onto a gurney. They can float the mattress over using just one hand — although HoverMatt recommends using two.”

- The replacement of all “traditional gurneys, which nursing employees have to push, with power gurneys that employees drive at the touch of a button” – not piecemeal, but in “every corner of the hospital”.

The problem in implementing these changes had an unexpected source: the nurses themselves. The equipment may be meant to save them from serious injury, but that doesn’t mean they will spontaneously use it:

[Six years ago] many of the rooms were already outfitted with lifts, but most nursing employees ignored them. “It was actually a laughing matter in the beginning,” Hilton said. The staff said, “‘Oh, no, lifts? They don’t work. Takes too much time.’ They were used to their old ways. [..] We have been taught for years that we manually handle patients”.

For that reason, the hospital focuses equally on training and coordination:

- Instead of sending employees “to an hourlong class, perhaps once per year,” as some private hospitals do, “there’s at least one employee on every unit, every shift, 24 hours a day, assigned to coach colleagues on how to use safe lifting technology”.

- A full-time coordinator functions as “safety champion” to remind the staff, but also the managers, of the issue. “Rank-and-file nursing employees said that without Hilton’s prodding, they wouldn’t remember to use the equipment”, while “hospital administrators told me that without Hilton’s constant lobbying, [..] they wouldn’t have invested so much money”.

The results are impressive: VA hospitals “have reduced nursing injuries from moving patients by an average of 40 percent since the program started,” and the injuries that employees do still suffer are less serious. Nurses know that the hospital has their back, and the hospital saves money:

Loma Linda spent almost $1 million during a recent four-year period just to hire replacements for employees who got hurt so badly they had to go home, Hilton said. Last year, the hospital spent “zero.”

|

When reporters talk, hospitals respond?No sooner had NPR aired the first part of its series, or Kaiser Pemanente responded. One of its hospitals was the subject of a case study in that first piece, after all. While downplaying the unfavorable 2014 court ruling, its statement highlighted the progress its hospitals have made “implementing a “no manual lift” environment to help reduce injury rates”. In two years’ time, Kaiser Permanente emphasized, “the rate of patient-handling injuries throughout our 21 Northern California hospitals declined by 23 percent.” Elsewhere, hospitals were quick to use the series to tout their own achievements. The Methodist Rehabilitation Center in Jackson, Mississippi, which treats patients with stroke, brain and spinal cord injuries, posted its own news story. Referencing the NPR reports, it elaborated on how “the state’s rising obesity rate” and “a failing economy [which] was keeping older nursing personnel in the work force” had been increasing the problem. However, the hospital reduced bodily injuries related to lifting and moving patients “by more than 80 percent since it began installing a 132-unit, ceiling-mounted lift system in 2010”:

While the lift system’s price tag of $759,000 was steep, the hospital explained, it would not just “benefit employee and patient welfare,” but also “eventually pay for itself”. The lifts “have already helped reduce Worker’s Compensation and employee replacement costs from $233,761 in 2009 to $2,097 in 2013 [and] the hospital expects to recoup its initial investment by the end of this year.” A month after the first four reports, NPR followed up with a fifth part focused on government regulation, or rather the lack thereof. But before that already, the Sidney Hillman Foundation presented reporter Daniel Zwerdling with its monthly Sidney Award. In an interview, Zwerdling summarized why he thought the story so important:

|

Unfortunately Anonymous

Unfortunately, the Mission Hospital horror continues with brand new injured faces, same old Mission Hospital Evil. One worker was sexually assaulted by another staff while at work. Mission denied her claim. They spend over $100,000 on private investigation fees to try to keep from having to do anything for her despite knowing she had PTSD as a result of the incident and incident was proven to have happened.

It’s a sad reality to be a nurse who gives your life to the hospital only to be abandoned and abused by them when you are injured. Another horrific case is brewing now…several, in fact and I am so angry and sad to know that.