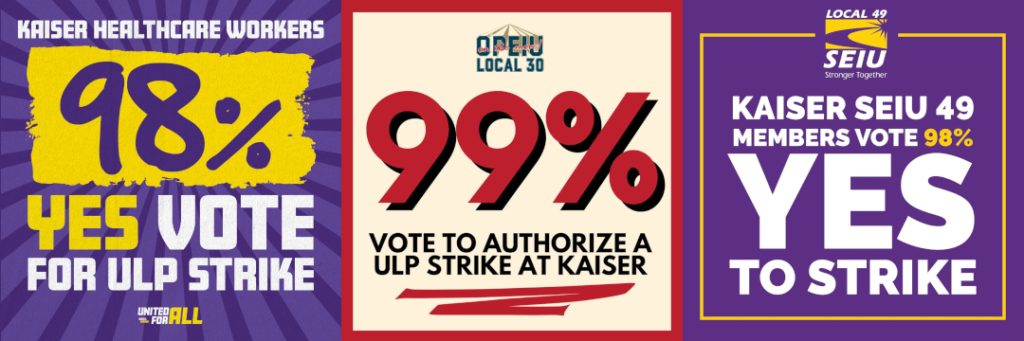

It’s the largest health care strike in U.S. history! Now that 75 thousand healthcare workers at Kaiser Permanente are on strike at hospitals and clinics across California, Colorado, Oregon and Washington, it’s time to re-up our post about strikes and nurses! But this time, we’ll get straight to the practical info.

We told you, after the huge nurse strike in New York City last January: “this wasn’t the first nurse strike even just in the last few months, and it won’t be the last”.

With half of U.S. hospitals recording negative profit margins last year, hospitals are on a mission to cut costs. But nurses are fed up, and they’ve figured out that strikes are an effective way to force their employers to address staffing ratios and inadequate wages. After all, the New York nurses got a 19% raise over three years, improved health coverage, and “wall-to-wall safe staffing ratios for all inpatient units”.

So what can you expect when you go on strike? What are the practical and financial consequences? What are the likely rewards? What happens if you don’t agree and cross the picket line? What are the immediate human costs of a nursing strike — and what is the potential upside for patient care in the longer term?

There’s another scenario that will come up too, and it’s going to involve you, your conscience, and your wallet. Whenever there’s a strike, strike nursing agencies are going to be offering travel nurses eye-watering amounts of money for strikebreaking jobs. What can you expect if you take up such an assignment? We’ll cover all that in this post.

What do strikes mean for patient care?

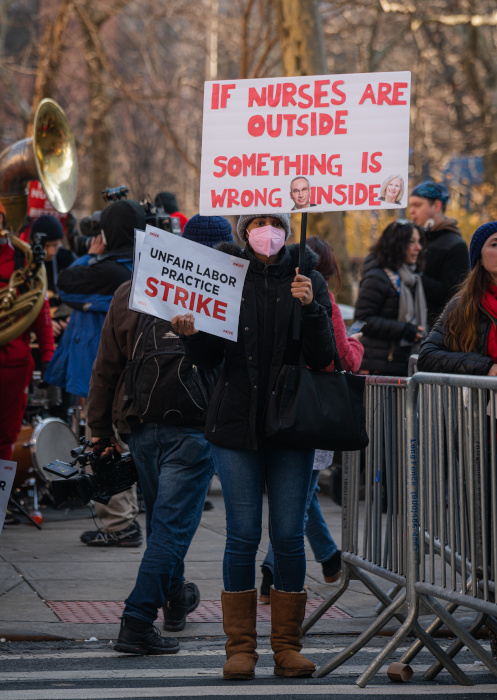

Let’s be clear, nurse strikes cause real turmoil in hospitals, no matter how many detailed notes they dutifully leave behind. During the strike in New York City ambulances were diverted, elective surgeries canceled, hundreds of patients transferred to other facilities, and people got pulled onto the floor who hadn’t done bedside nursing in years.

For emergency cases there will be a patient protection task force or emergency standby committee of RNs which can approve individual instances where a striking nurse goes in to stabilize a patient. But one historical study found that in-hospital mortality increased by a shocking 19% during strikes, costing 138 lives over twenty years in New York state.

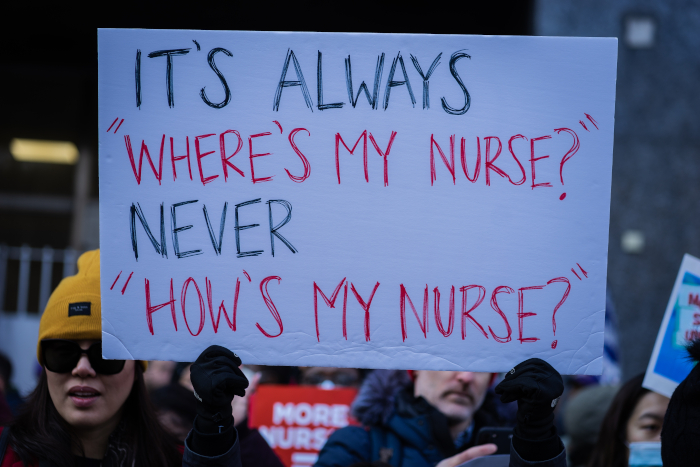

The question is how many deaths were avoided in later years thanks to patient safety improvements that were won in those strikes. NYSNA President Judy Sheridan-Gonzalez argued that nurses strike to save lives: when “months and years of meetings, documentation, evidence, petitions, letters, research, protests, speeches, essays, negotiations, pickets, rallies and media outreach” fail to achieve what’s needed to take care of patients properly, “our employers leave us with no other choice”.

So what do nurses do? Vote for a strike and join the picket, or break ranks? Take a highly-paid job as a strike nurse, or refuse to work as a “scab”?

What can you expect when you go on strike?

The good news is that federal law bans employers from firing you just for taking part in a lawful strike. In the unlikely case they’d try to anyway, you’d have a strong case for wrongful termination.

There are some details to pay attention to, though: workers who go on strike over unfair labor practices generally cannot be replaced at all, while workers who take part in an economic strike can find themselves permanently replaced, with only the right “to return to a similar position or be the first called when new positions become available”.

That’s not going to happen during brief strikes though, and this is obviously a top priority for the union — in any deal to end the strike they’ll demand the right of nurses to return to their jobs.

You also don’t have to worry about being sued over patient abandonment when you take part in a lawful strike — at least if you’re part of a union or live in a state where nurse unions have a presence. In theory it’s a different story in nonunion states where nurses could “expose themselves to a bevy of legal implications,” but strikes are pretty rare there. “Wildcat” strikes and strikes that are judged as unlawful for reasons like misconduct are different too, which is why unions will urge strikers to stay disciplined and professional!

A strike will only be called after the represented nurses vote for it, and some legal rules apply to when and how strikes can be called. Healthcare unions must give the employer ten days’ notice to make sure they have enough time to arrange replacement staff. That’s why you read so many stories about last-minute deals during those ten days!

Many collective bargaining agreements also include a guarantee that workers won’t go on strike for as long as the contract lasts, which is why you see strikes erupt right after an agreement expires.

Striking can be expensive: you will need savings!

Wherever you live, going on strike will cost you — at least in the short term! It doesn’t matter how reasonable your goal is, or how overwhelming a majority of the nurses voted for the strike, your employer is unlikely to pay you for the days you’re on strike.

Financial consequences can extend beyond just those days too. When 8,000 nurses at Sacramento’s Sutter Health went on strike for just one day last April they were locked out for the rest of the week as well, losing a whole week’s wages. The employer argued it had no choice: the replacement travel nurses were on contracts with five days of guaranteed staffing.

You can’t apply for unemployment benefits either, generally speaking. If a strike lasts for more than a day or two and you risk missing a debt or mortgage payment, you should inform your bank or creditors ahead of time. They’re a lot more likely to work out a deferral to protect your credit rating if you’re proactive about it.

The union might be able to provide some financial support from its strike fund. AFT Local 5017, for example — a union of more than 5,000 health professionals in Oregon and Washington — says that striking nurses would “have access to an interest free loan through the AFL-CIO credit union” and people who face an “extremely difficult” situation could get aid from a hardship relief fund.

Unions which don’t have similar resources often launch fundraising drives so they can still provide some financial assistance. They might also have a committee dedicated to helping striking nurses find alternative employment during the strike.

Finally, your health insurance could be at risk, at least for the duration of the strike (your benefits should be restored once you return to your job). When nurses at Stanford Health Care went on strike last year to demand safer staffing, higher wages and better mental health support, their employer warned them they’d lose their health coverage if the strike went on through the end of the month.

Many employers won’t go this far and the union called it “beyond cruel and insulting,” but Stanford executives pointed to the union’s own contingency manual, which explains that nurses can pay out of pocket to continue their health coverage through the COBRA federal program. (You can apply for COBRA coverage retroactively too, and some large unions even make COBRA payments on behalf of their members — not sure if that’s true for any nurses’ unions though!)

Why you might regret crossing the picket line

Do you have to join a strike at your facility? The answer depends — on where you live, for example, or the terms of the union contract. But refusing when your colleagues overwhelmingly voted for the strike can have serious consequences. One does not simply cross the picket line!

If you work in a state with mandatory union participation, you might not have much choice. If you’re a member of the union, participation is mandatory (and they’ll expect you to show up for your share of picket duty too: “a strike is not a vacation“). The union can impose a fine on wayward members, and of course you’d lose your union benefits. While employers will often encourage you to cross over, they might also choose to lock out union members.

But perhaps it’s not the financial sanctions you have to worry about most? You risk making enemies out of your colleagues — and even future colleagues at other hospitals who belong to the same union. Bitterness will linger. One nurse redditor recalled working at a hospital where “certain employees were ostracized by other employees because they crossed the picket line a decade ago”.

In the end, you should also evaluate the immediate costs of going on strike against the potential upsides for your wallet as well as your working conditions if it succeeds. Your colleagues might remind you that healthcare workers who are union members earn an average $180 more per week than others: collective action has its benefits!

What can you expect from working as a strike nurse?

Even where staff nurses don’t have much of a choice about joining a strike, travel nurses are free to move in. And employers will pay them very, very well for it. There are whole staffing agencies that specialize as strike nursing companies, and they will warmly welcome your application.

Let’s be honest: the one reason why travel nurses would take on an assignment as a strike nurse is because of the money. It involves some of the highest pay in the business! You can routinely expect to make twice as much as normally, with travel and accommodation costs covered and a guaranteed minimum number of hours.

Just look at what happened in New York City, where hospitals were offering travel nurses an eye-watering $300 per hour to staff the NICU/PICU. During the Minnesota strike last year, ‘scab’ nurses could make up to $8,000 in five days: the three days of the strike plus two days of training.

Strike nursing beyond the dollar numbers

Working as a strike nurse also gives you the same kind of opportunities for professional growth as any travel nursing job: you get to work in very different settings and environments, acquiring valuable experience. But taking a job as a strikebreaker comes at a price.

First off, there’s a lot of uncertainty involved. You have to be ready to take assignments on short notice: have a go-bag ready! That includes any and all paperwork you’d need — maybe consider medical error coverage too. Flexibility and improvisation are the name of this game. Don’t expect to take your family with you; you might even be rooming with another nurse. And of course you need to be licensed to work in the state in question, though strike nursing agencies sometimes help nurses with licensing and certification requirements.

On the flip side, the strike could end at any moment, so don’t make any plans! You could find out you’re no longer needed on the day you were about to travel. If you’re already at the destination you’ll get your travel costs and guaranteed hours covered, but then you’re on your way back home. The opposite could happen too: one strike in Minnesota in 2016 lasted 41 days, and some strike nurses kept working throughout.

Training and orientation will be extremely limited. You’d likely work very long hours, up to 50-60 a week. One travel nurse who worked through a strike last year declared she wouldn’t ever do it again: “I’m exhausted, my energy is low, I feel out of shape and emotionally spent”. And working conditions will be the luck of the draw: management could come out in force to support you, or you could be confronted with the worst of the conditions those nurses outside are protesting about.

They’ll call you a ‘scab’ — are they right?

Finally, there’s the elephant in the room. You will be working in a tense environment, snuck into the hospital out of sight from the picket lines, because opinions about your role will be, how shall we put this… mixed. At best.

An old discussion on AllNursing.com illustrated how differently those on strike might perceive your work. “I would dumpster-dive before I would undermine other nurses,” one nurse with 42 years of experience opined. “A scab by any other name is still a scab,” another agreed. But one Med Surg nurse had a more nuanced take:

“The hiring of replacement nurses is something the striking nurses know must occur. They know patients cannot go completely without care. I’m in a union and if I went on strike I would wish only the best for the RNs brought in to take care of people.”

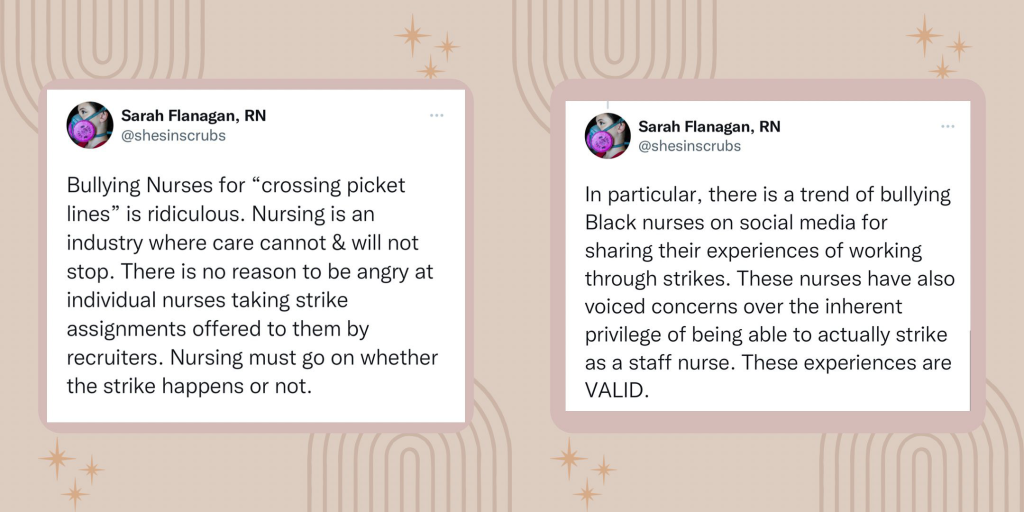

On Instagram, RN Sarah Flanagan made the same argument and also urged nurses to consider that some nurses simply can’t afford to go on strike:

But many others will disagree, pointing out that it’s patient care they are defending with their strike, and their wage demands will help the less well-off nurses most of all. Replacement nurses won’t be able to adequately take care of their patients, they’ll argue. “They don’t know our policies and protocols,” a striking nurse in Minnesota complained to CBS: “They don’t know where stuff is, how our department works, how our patients work and you don’t learn that in a few days of training”.

Instead, they will insist, the best way to safeguard patient safety is for management to meet their desperate demands, so they can go back to the work they love. And barely trained strike nurses who are shipped in overnight just help the employer avoid doing so.

Your job, your profession, your choice

As a travel nurse who flies in and flies out again, you’re a free agent. You won’t have to deal with the ostracization a local nurse who crosses the picket line might face. Perhaps the wage demands seem overblown to you anyway, when you compare them with nursing pay in your home state. However quickly the employer comes around, you might say, there are always still going to be some days where strike nurses are needed. Not every patient can be transferred to another facility, and none of it is their fault. And maybe you just really need the money!

But before you take on an assignment as strikebreaker you should definitely look into what triggered the strike — if nothing else to get a better sense of what you’re getting into — and it’s worth reflecting on why so many nurse strikes are happening. It’s no secret that the profession faces a crisis. Nurses are underpaid, undervalued, and do dangerous work. Understaffing is causing burnout all over the place and an exodus from the profession; and the striking nurses are trying to do something about it all.

On the picket line in New York City, nurses said they worried about their patients inside; they just felt they had no choice exactly because they cared about patient safety. Montefiore nurse Ana Villeda told the New York Times that the ED “often resembled a .. parking garage, with rolling stretchers stacked several deep,” and recounted how one patient had waited in a chair for three hours before staff realized he was having a heart attack. “Every time I go into work,” striking nurse John Adriel added, “truly I’m scared for my license.” And that’s not a job anyone should have to do.